Why Food Prices Are Rising

Food prices are out of control and everyone knows it. Since the pandemic, shopping at a grocery store or eating at a restaurant has become an increasingly expensive experience. So what's going on?

This article is more than 2 years old

Food prices are out of control and everyone knows it. Since the pandemic, shopping at a grocery store or eating at a restaurant has become an increasingly expensive experience. So what’s going on? Why are food prices rising? industry. The factors are plenty, with enough blame to cover just above every part of the food industry.

Here’s everything we know so far about why your food prices are rising.

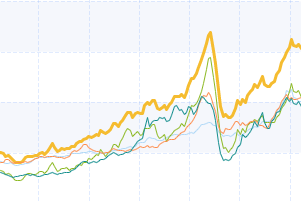

Food prices in July of 2021 alone, have risen 0.7%. On the surface, that may not seem like much, but over time, that slow tick adds up tremendously. In the decade prior to this crippling COVID pandemic, groceries had a year-over-year price increase of about 1%. That is one year. That puts July’s bump well over double in one month compared to the yearly average prior to COVID.

In the past year, since COVID became a global reality, grocery prices have risen 2.6%. The food price increase has been on a steady incline and unfortunately, this could be our new reality. Phil Lempert is a food trend expert and analyst who also goes by the moniker The Supermarket Guru and he says via Fortune, “We’re going to continue to see price increases, probably for the next two years or so.”

Experts say there are plenty of reasons for the food price jumps at the supermarkets that include how COVID has affected our global food supply chain, the mass labor shortages, and even climate change.

Rising Commodity Prices

So, let’s dig a little bit here on what’s going on with rising food prices. Agricultural commodity prices have been jumping over the past year caused by the growing seasons surrounding conditions as well as buying trends. For example, China has been purchasing a number of commodities, including soy, which is often seen in animal feed. This definitely pushes up the price, which jacks up the chicken and pork prices as they are now more expensive animals to raise.

“Climate change is greatly affecting the foods that we grow and how we grow them. Long term, we will see a lot more indoor farming, but that takes hundreds of millions of dollars and time to build,” Lempert says of rising food prices. The immense and numerous forest fires in California have damaged vineyards, while in Brazil, unsteady rain, drought, and sometimes even frost have destroyed coffee production.

A Transportation Nightmare Impacting Food Prices

The raw price of raising animals and producing crops is only a small fraction of what consumers pay at the grocery store for food. They also need to pay for transportation, energy, and labor costs. These are prices that have also seen a sharp increase and they get passed along into the prices you pay for food. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, gas prices alone in the past year have risen 41.8%. When the costs to transport food go up, those costs get passed on to you, the consumer.

The pandemic has wreaked havoc on transportation. “We don’t have enough truck drivers,” Lempert laments. “We’ve been talking probably for three or four years that the truck driver workforce is aging, retiring, and there’s not a lot of people who wake up in the morning who say, ‘I want to be a truck driver.’”

Case in point, major food producer Tyson. They recently issued another (there have been plenty this year) price increase. Food buyers will now see a price jump in pork of 39%, beef will get a 12% increase, while chicken will now see a 16% lift. Those are no small numbers.

According to the Supermarket Guru, those food price increases are partially due to the fact that refrigerated truck transportation has gone up by 12%. These are costs, he notes, that have to be passed along somewhere. Guess who pays.

No One Wants To Work

Then there are the labor costs. Companies are now truly beginning to feel the pinch as the labor shortage across the globe is taking its toll. The way companies are trying to get people to return to the workforce, especially in the food production and retail industry, is to raise wages. These costs have to go somewhere and they’re going into higher food prices. “It’s probably the case that if we want the kind of labor that we’ve come to expect in the food service sector and food processing, then [employers] are probably going to have to pay a little more,” Lempert says.

Of course, one of the biggest food pricing issues we may be facing comes from where our supply chain starts. The COVID pandemic has left the entire global food supply chain with a massive labor shortage that, like the food prices, doesn’t seem to have any relief attached to it.

In the U.K. food prices are rising as farmers find themselves having to dump their milk because there are no truckers to pick it up. In Brazil, their normal 90-day harvest took 120-days this season as the pandemic hit them hard. The army in Vietnam has been helping rice harvesters. In the U.S., meatpackers have resorted to offering Apple watches in hopes of luring new employees.

“We have family-wage, great jobs that have been open, that we’ve been recruiting really hard for and have had trouble filling,” says Tillamook County Creamery Association CEO, Patrick Criteser through Supply Chain Brain. “With the inflation, we’re seeing in the business and the inflation that we’re seeing at the farm level, it’s going to translate to the shelf.”

But to emphasize how difficult it has been to find new employees, Criteser says they were so short on workers that a Tillamook board member had to skip an operational meeting so he could get out to the fields and help. When board members are forced milk cows just to get cheese on your table, it makes sense that food prices might go up.

The labor shortages continue to be felt everywhere. Shrimp production in southern Vietnam, which is one of the world’s top exporters, has dropped 60-705 since pre-pandemic numbers. The world’s number 2 palm oil producer, Malaysia, has lost nearly 30% of its edible oil. That means an increase in cost not just in palm oil, but also an increase in price in any food that has palm oil in it as an ingredient.

“I have been in this business since the ’80s, but I have never seen a situation like this,” says Michele Ferrandino, a farmer in Foggia, Italy. “Tomatoes are very perishable goods. There were not enough trucks to transport the crop to the processing plants, in those crucial days.” As a result, a fifth of southern Italy’s tomato production has been lost, raising food prices on everything that needs tomatoes in it.

It’s hard to say that we have reached a crossroads because that would mean we have choices. We don’t. Food and grocery prices are tied into everything above and if we first can’t get a handle on bringing workers back to the fields, the processing plants, the transportation companies, the grocery stores, we are going to continue to feel the rising pinch at the checkout lane.