Why Some People Get Urinary Tract Infections More Often Than Others

New studies are pointing to an immune response behind the propensity for frequent urinary tract infections.

This article is more than 2 years old

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are one of the top five reasons people visit urgent care centers. These common bacterial infections affect women more often than men, and some women seem to suffer from them far more frequently than others. The reasons for frequent UTIs used to baffle healthcare providers, but new studies are pointing to an immune response behind the propensity for frequent urinary tract infections.

Between 50 and 60 percent of women will have at least one urinary tract infection in their life. Around 25 percent of women have recurrent UTIs, defined as having two infections in six months or three in one year. While most of these infections are limited to the lower urinary tract (the bladder and the urethra) and respond well to antibiotics, some can spread to the kidneys and cause serious health problems.

UTIs may not cause any symptoms, but they usually announce themselves with a burning feeling while urinating. Strong urinary urgency coupled with cloudy, discolored, or strong-smelling urine is another common sign of a urinary tract infection. Many women experience pain and heaviness in the center of the pelvis, especially around the area of the public bone.

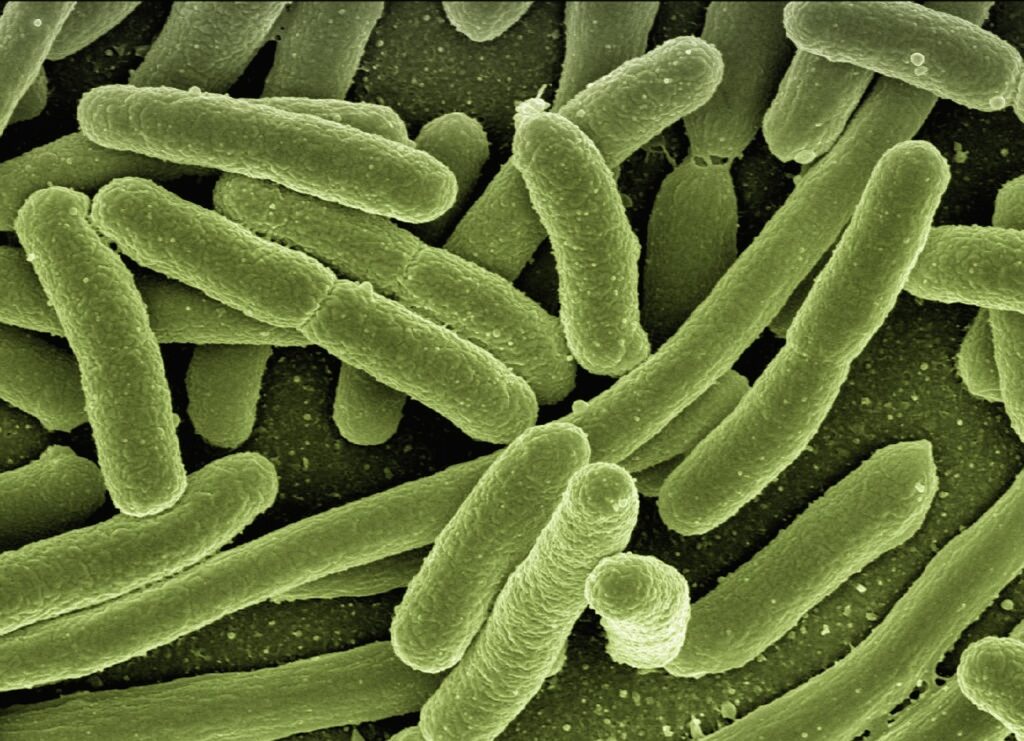

Women are more prone to urinary tract infections than men because the urethra is shorter and closer to the anus. This makes it easier for E coli and other bacteria from the lower digestive tract to enter the urinary tract and cause infection. This bacterial transfer is why women with frequent UTIs have long been advised to wipe front-to-back, and to urinate immediately after sex.

However, Washington University microbiologist Scott Hultgren says the new research offers a better explanation for recurrent urinary tract infections. “These people suffer from thinking they’re doing something wrong, that they’re wiping wrong or their hygiene is wrong,” he said. “This paper explains perhaps why they’re having these problems and that it’s not their fault.”

Research published in Nature Microbiology last week found that urinary tract infections can actually alter the DNA in the cells lining the urinary tract. Cells with altered DNA then change size and set off an immune response that makes the cells more susceptible to infection. According to NPR, these DNA changes are known as epigenetic modifications or markers that are placed onto DNA and lead the cells to change inside.

“It’s not changing the [DNA] sequence, but it’s changing the way in which the DNA is being read,” said Tom Hannan, an immunologist from Washington University and one of the overseers of the study. He also said that a body that has not seen an infection is like an open book. Epigenetic modifications are like page markers.

These modifications tell the body’s cellular machinery where to find the instructions for responding to an infection. Ordinarily, that response is meant to clear a single infection, but when it does, it causes problematic cellular changes. These lead to “more severe and chronic infections that actually make the subsequent exposures worse,” says Hannan.

Hultgren, Hannan, and their colleagues infected mice with E coli to give them urinary tract infections. As with humans, some of the mice were more prone to repeated infections after the initial UTIs were cured with antibiotics. When they compared cells from both types of mice, they found the ones with recurrent UTIs had smaller cells with differentiation defects.

The researchers admitted that it’s not known if their findings are translatable from the lab to real life, or whether these epigenetic modifications happen in humans. So new treatments based on this discovery are probably not coming anytime soon. However, the insights gained may eventually offer a permanent fix to the problem of recurrent urinary tract infections.