The Least Deserving MLB Hall Of Famers

The Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York, is an institution that ostensibly honors the best players in MLB history — but over its history, this definition has become distorted and skewed so frequently that it’s hard to know what the Hall stands for at this point.

From cronyism that enshrined undeserving players early in its history to banishing deserving players for questionable reasons, the Hall of Fame is an undeniably imperfect institution. The following players all had productive careers — but it’s highly questionable whether they should be enshrined at Cooperstown.

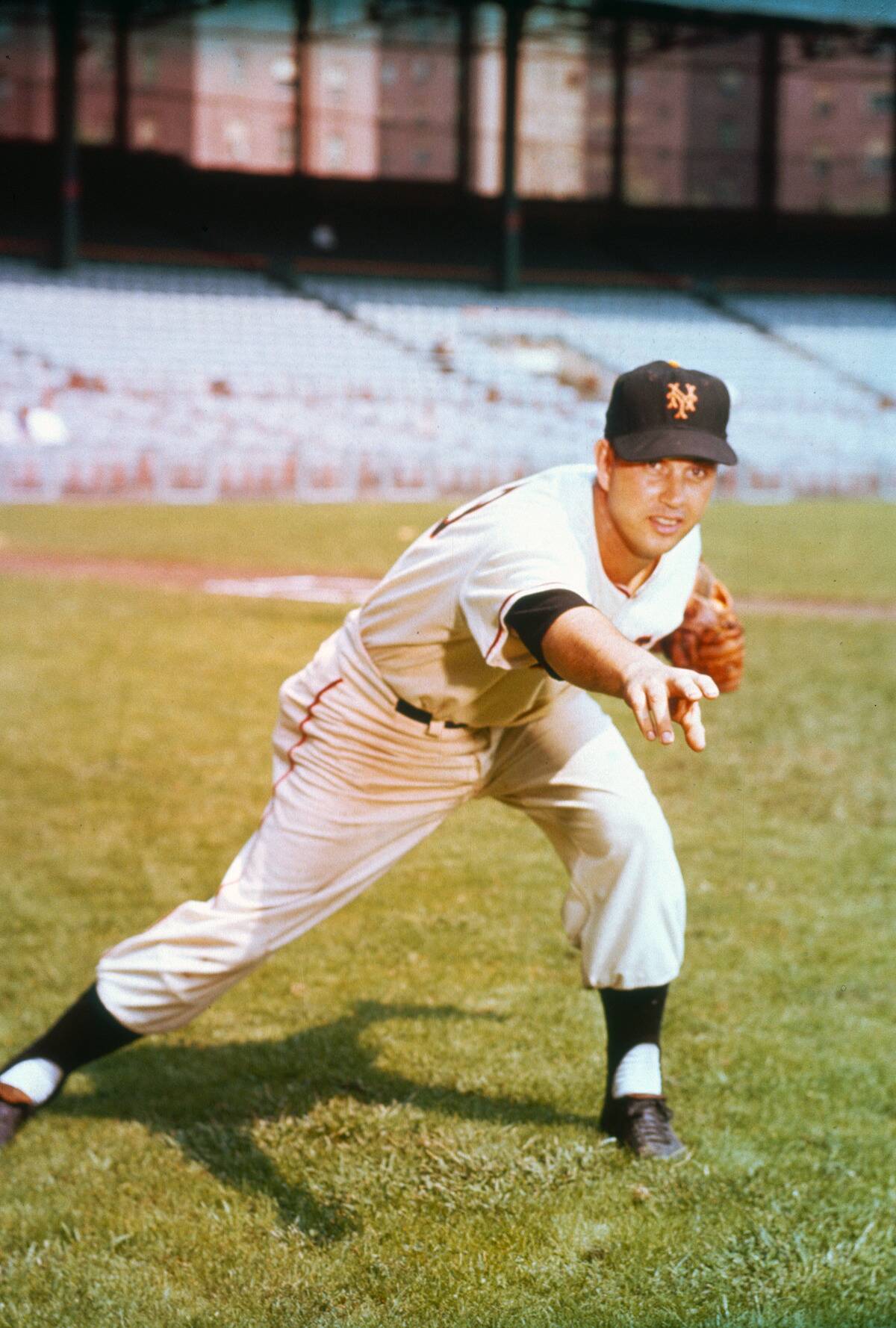

Bill Mazeroski

Bill Mazeroski established a stellar defensive reputation during his playing days, racking up eight Gold Gloves. While an impressive achievement, his defence alone doesn’t make him Hall-worthy, nor does his below-average offence.

Mazeroski was elected by the Veterans Committee in 2001, decades after his playing career ended. It’s likely that his iconic 1960 home run, which secured the World Series for his Pirates over the New York Yankees, clinched the nomination, as his true body of work was clearly not worthy of Cooperstown.

Hoyt Wilhelm

Hoyt Wilhelm was a household name during his long career, and he was a true trendsetter as one of the earliest examples of a true relief pitcher. Indeed, he was the first pitcher to rack up 200 saves and 1,000 games, and he played for 20 years.

Still, Wilhelm’s production — though always steady — was never particularly elite. His raw totals have been eclipsed time and time again in the years since his retirement, making Wilhelm’s career stats look pedestrian. While there’s little doubt that he was influential, it’s hard to make a case for him being one of baseball’s best.

Lou Brock

Long before more modern speedsters like Rickey Henderson, Lou Brock set the pace with his blistering speed on the basepaths. When the Cardinals outfielder retired, he’d racked up 938 career stolen bases and was as well-known as any player in baseball thanks to his visually exhilarating style of play.

Despite this, Brock’s numbers reveal that outside of his speed, he was a fairly average player. Modern defensive metrics rate both his offence and defence as mediocre.

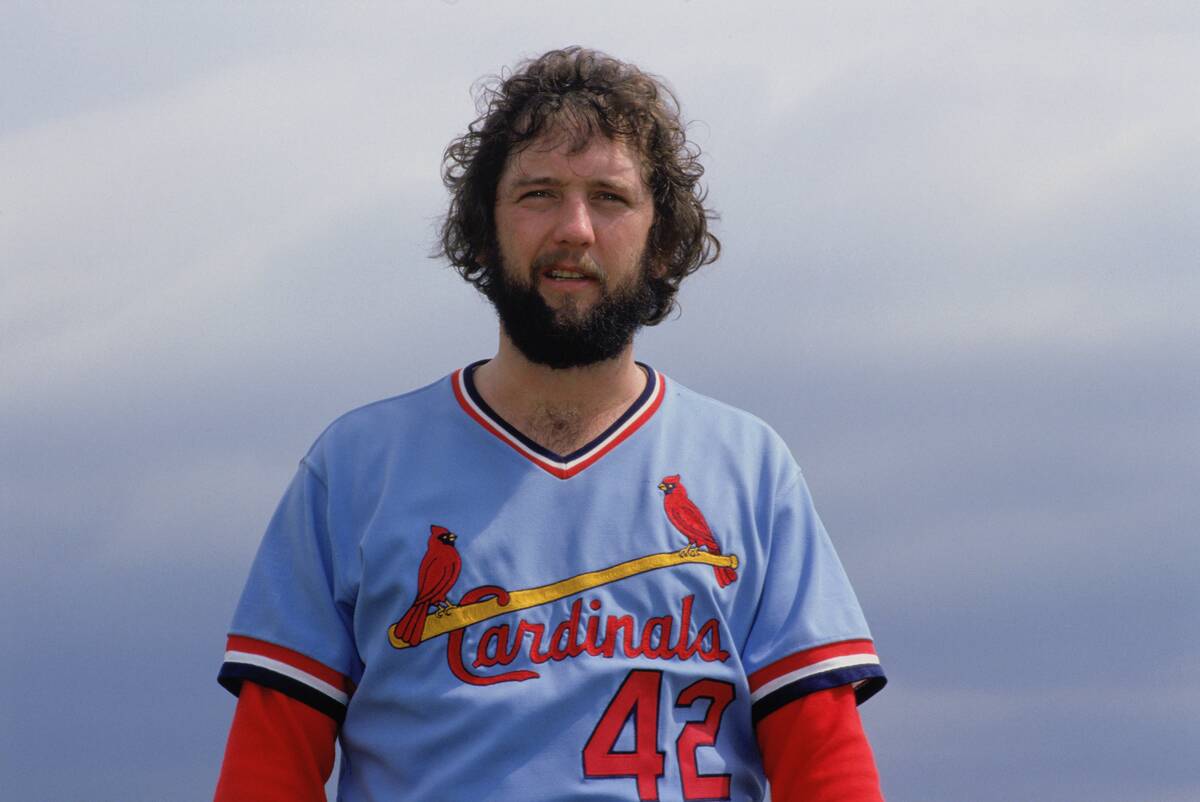

Bruce Sutter

Thanks to his incredible split-finger fastball, Bruce Sutter transformed the closer role, earning 300 saves — along with the 1979 Cy Young Award — in the process. During his career, he was viewed as baseball’s top closer, but his stats are fairly pedestrian by modern standards.

Sutter saved a lot of games, but also blew a lot of saves relative to his peers. He also had the luxury of a low workload, as he rarely surpassed 80 innings pitched in a given season. While Sutter was a pioneer in the closer role, he’s been outdone by countless closers in the decades since.

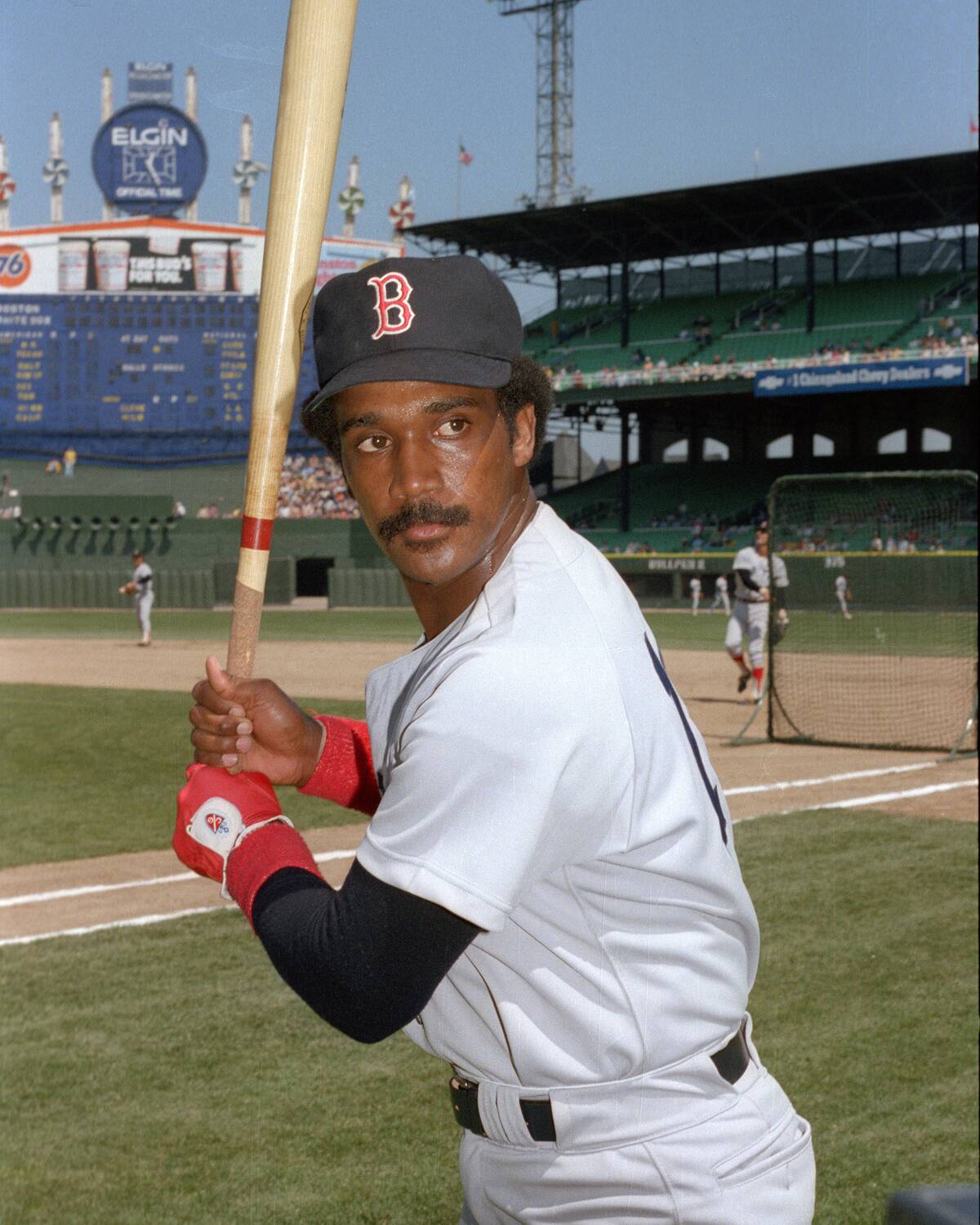

Jim Rice

Jim Rice is regarded as a Boston Red Sox legend, but his career stats raise questions over why he was inducted into Cooperstown. While he had a strong peak in the late ’70s and put up good power numbers, he was weak defensively and struggled to draw walks.

Rice was inducted after 15 years of eligibility, just barely clearing the 75 percent voting threshold in 2009, an indication of hesitation on the part of Hall of Fame voters. Players such as George Bell and Ron Gant are not in the Hall, but had more sustained production across more seasons than Jim Rice.

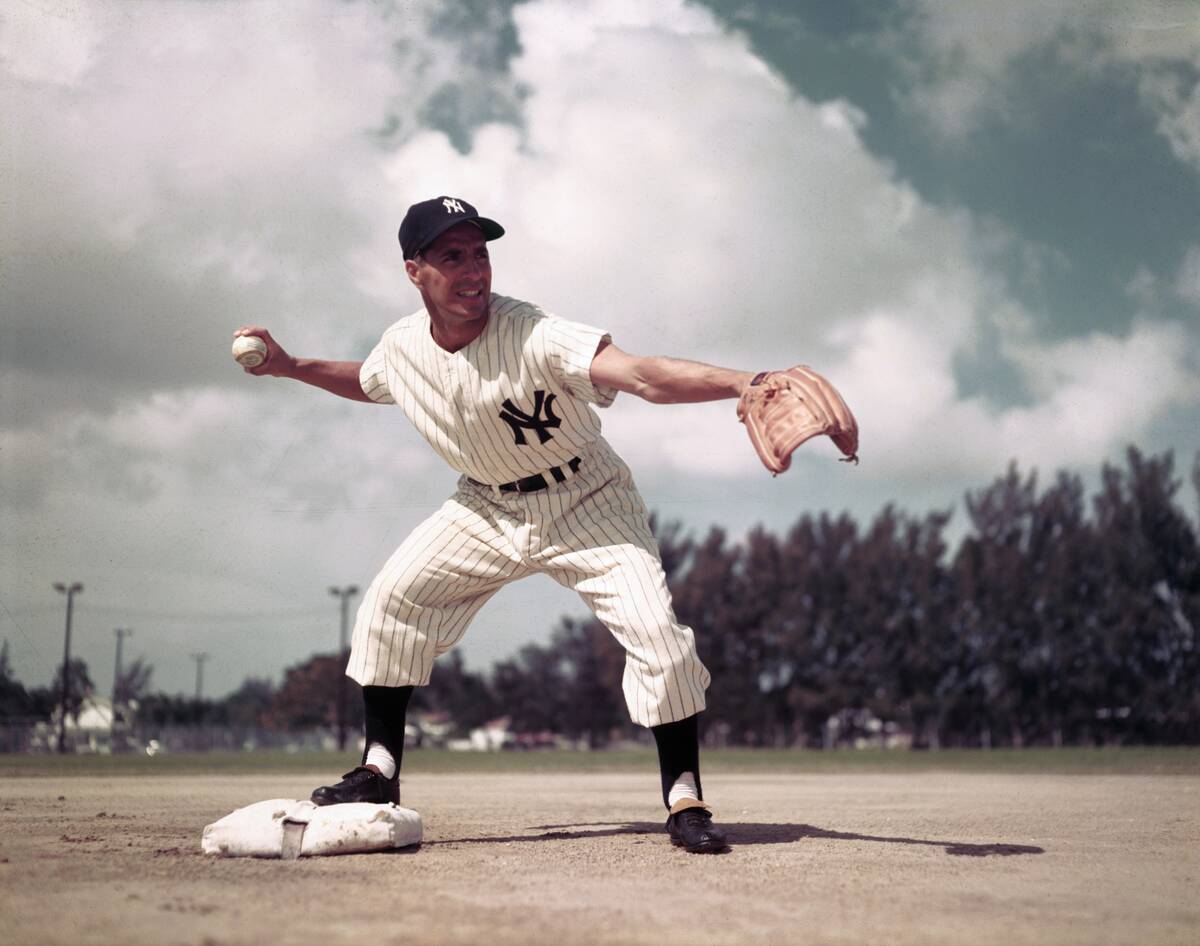

Phil Rizzuto

Phil Rizzuto is better remembered as a beloved Yankees broadcaster than he was as a player — which makes it baffling that he was inducted as a player and not as a broadcaster. His career stats fall well short of other shortstops in Cooperstown, and even his 1950 MVP award is puzzling given his stats that season.

While he’s no doubt a beloved part of Yankees lore and had a good playing career, many fans agree that he was inducted more for his charisma than for his playing ability.

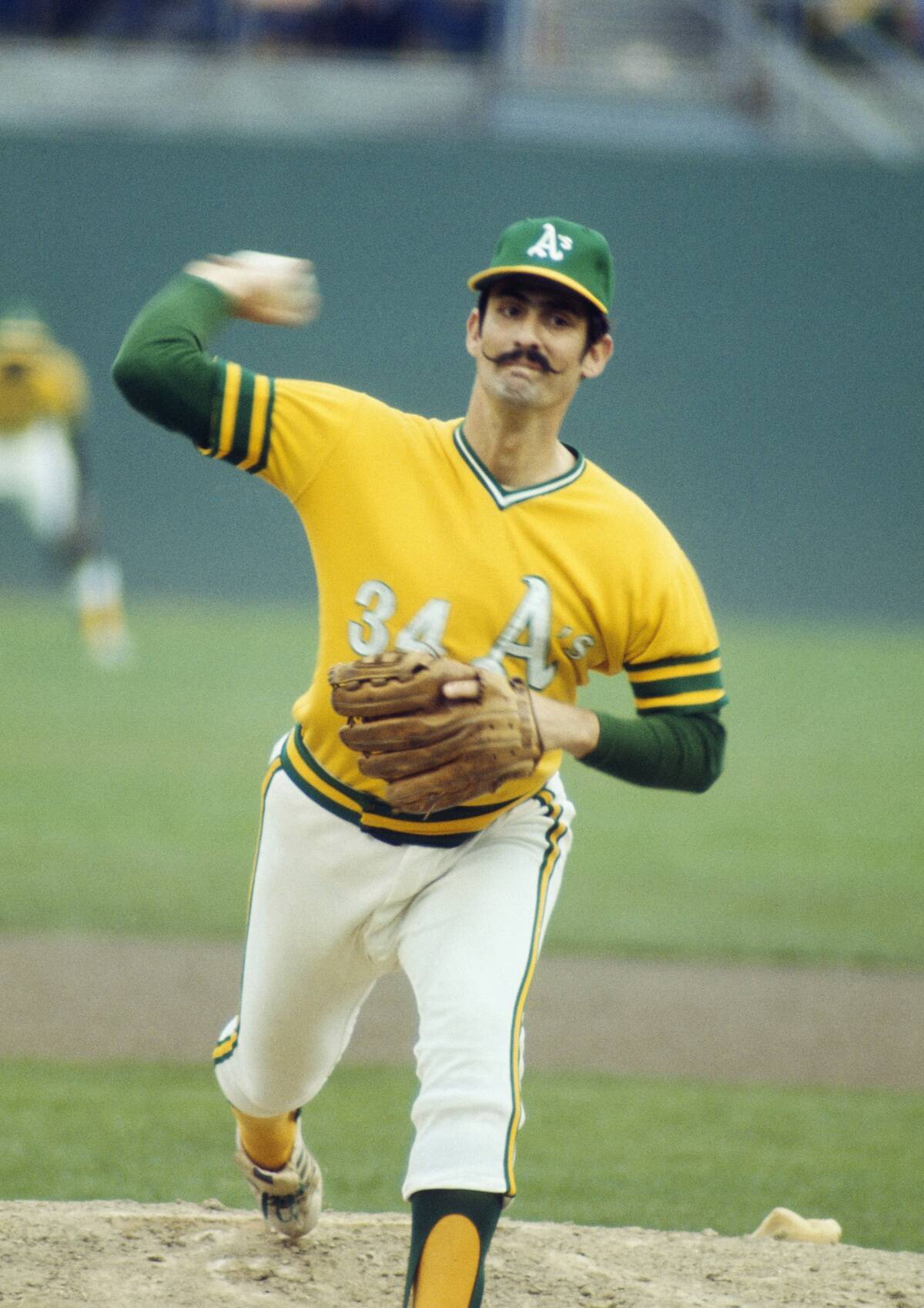

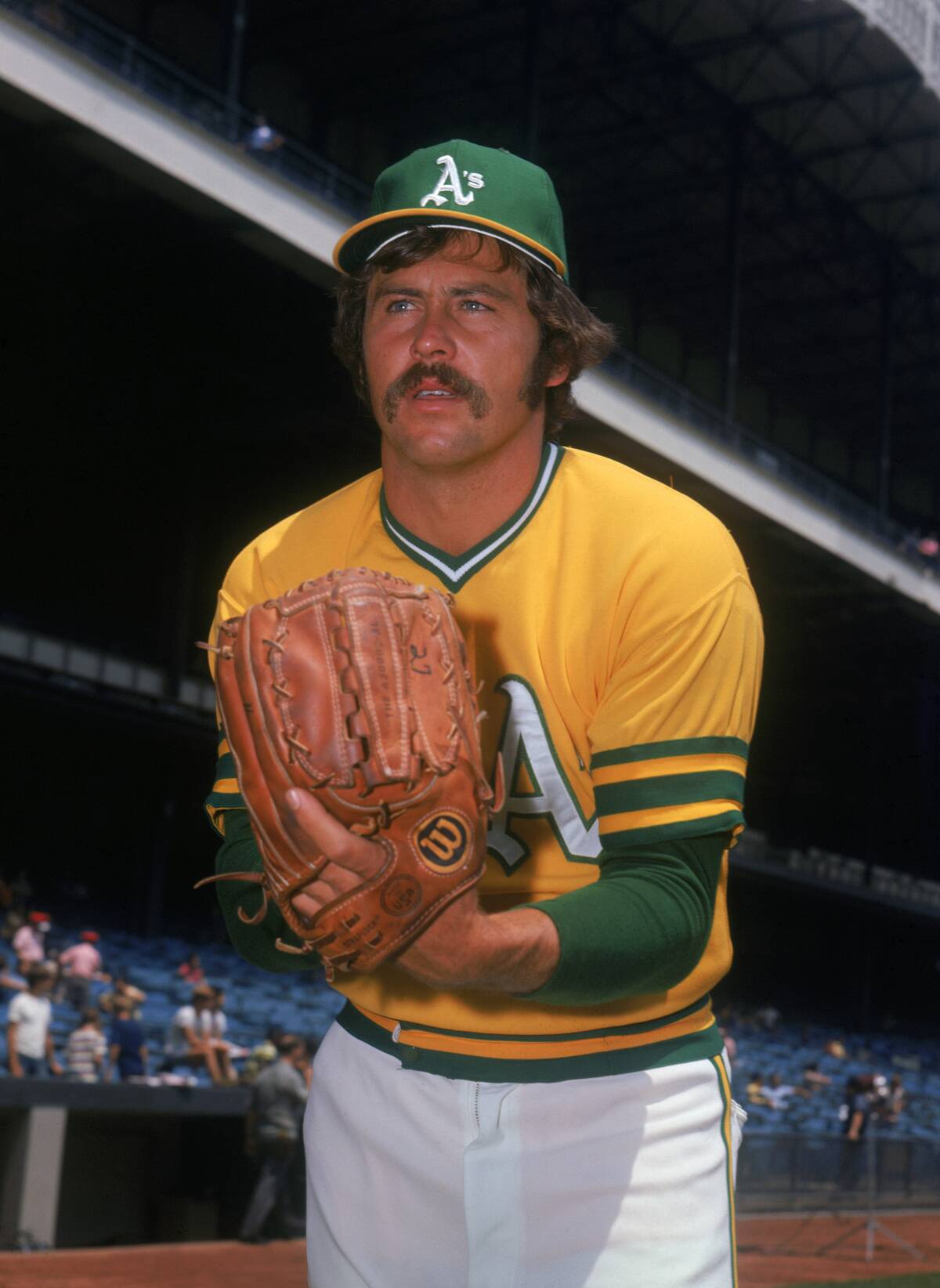

Rollie Fingers

There’s no doubt that Rollie Fingers was an elite closer for his era, and a run with the Oakland A’s dynasty of the 1970s helped to cement his legacy. Still, his career numbers — a WAR of about 24.4 and fewer than 1,000 innings pitched — are fairly modest compared to other relievers in the Hall.

Fingers received about 81 percent of the vote from the Baseball Writers’ Association of America, indicating some ambivalence among voters. While he may have been the archetype of a closer, he wasn’t necessarily a standout.

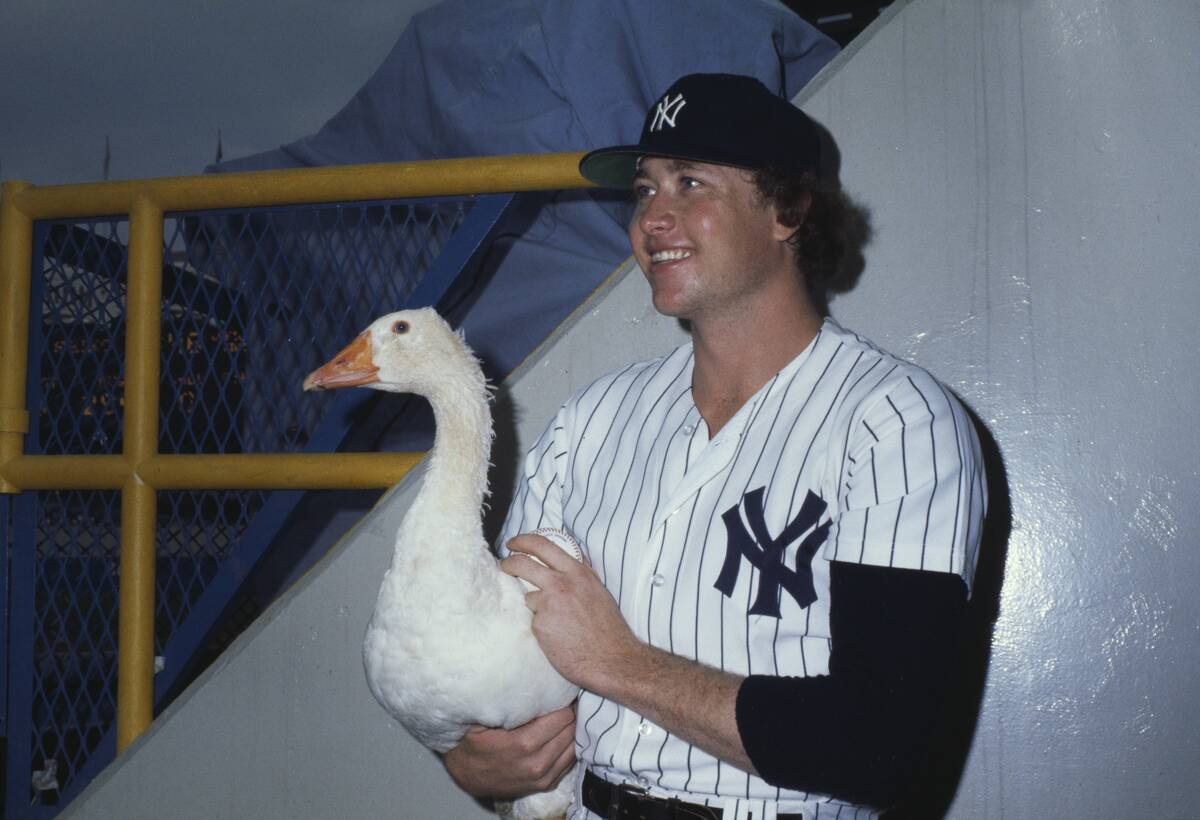

Rich “Goose” Gossage

Goose Gossage earned seven All-Star selections on the back of a blistering fastball and 310 career saves. But Gossage, much like his contemporary Rollie Fingers, didn’t put up career numbers that would necessitate enshrinement in Cooperstown.

Gossage was elected to the Hall in 2008, more than 15 years after Fingers. It could be argued that voters felt they needed to include him if they’d already inducted Fingers, a very similar player who played during the same era.

Tony Pérez

Tony Pérez was a linchpin of the “Big Red Machine” Reds of the ’70s, and he did put up solid career numbers, including 379 career home runs. It’s worth noting, however, that Perez was a first baseman — a position where power hitting is the expectation — and his numbers fell behind fellow first basemen of similar eras.

It seems that Pérez’s induction in 2000 via the Veterans Committee came as a result of nostalgia rather than statistical dominance, because his numbers make it clear that he was a great complementary piece more than he was the central axis.

Catfish Hunter

Catfish Hunter had it all — a strong career wins/losses record, two Cy Young Awards, a perfect game, and a memorable nickname to boot. While Hunter’s prime was impressive, he fell off steeply in his later years and put up a career WAR of 60 or so, right around the median for Cooperstown.

Compared to contemporaries like Jim Palmer and Ferguson Jenkins, Hunter had a truncated prime — one that wasn’t long enough to put up numbers that were truly Hall-worthy.

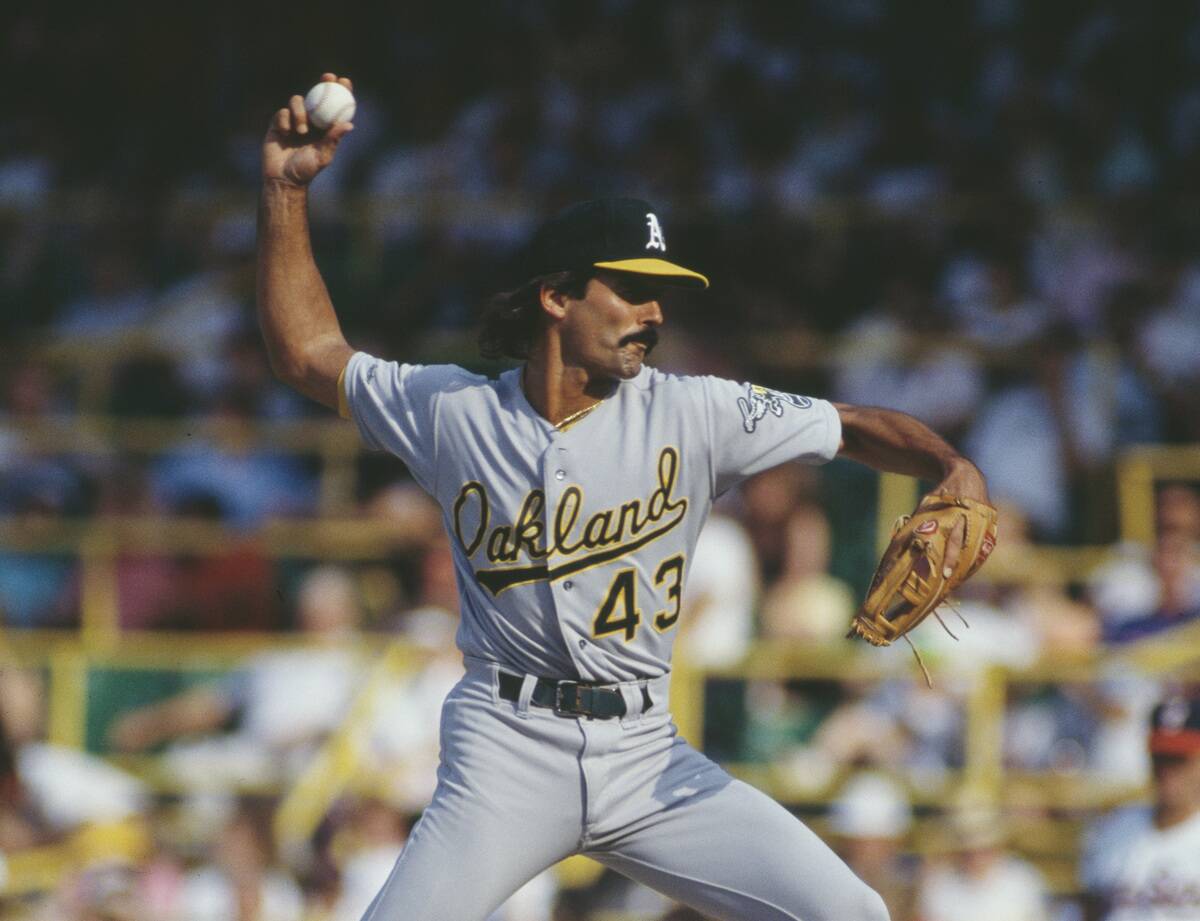

Dennis Eckersley

Eckersley starred as a starting pitcher, experienced setbacks, then reinvented himself as one of the most feared closers of the late ’80s and early ’90s — the rare pitcher to achieve such significant dominance in both roles.

In total, Eckersley’s numbers make him a relatively safe addition to the Hall of Fame, and if he’d spent his whole career in one role, he’d probably be a Cooperstown lock. Still, the fact that he essentially had two different careers means that his stats in either category look somewhat incomplete, given his longevity.

Andre Dawson

Andre Dawson, known as the “Hawk”, put up 438 home runs and 314 stolen bases across his career, along with two MVP awards. While this all sounds Hall-worthy, he put up a surprisingly low career WAR of 62 or so.

Dawson was an under-appreciated star during his career, and many would argue that his 2010 induction into Cooperstown was long overdue. However, a relatively short period of peak production and inflated narratives surrounding his Hall status after his retirement call his enshrinement into question.

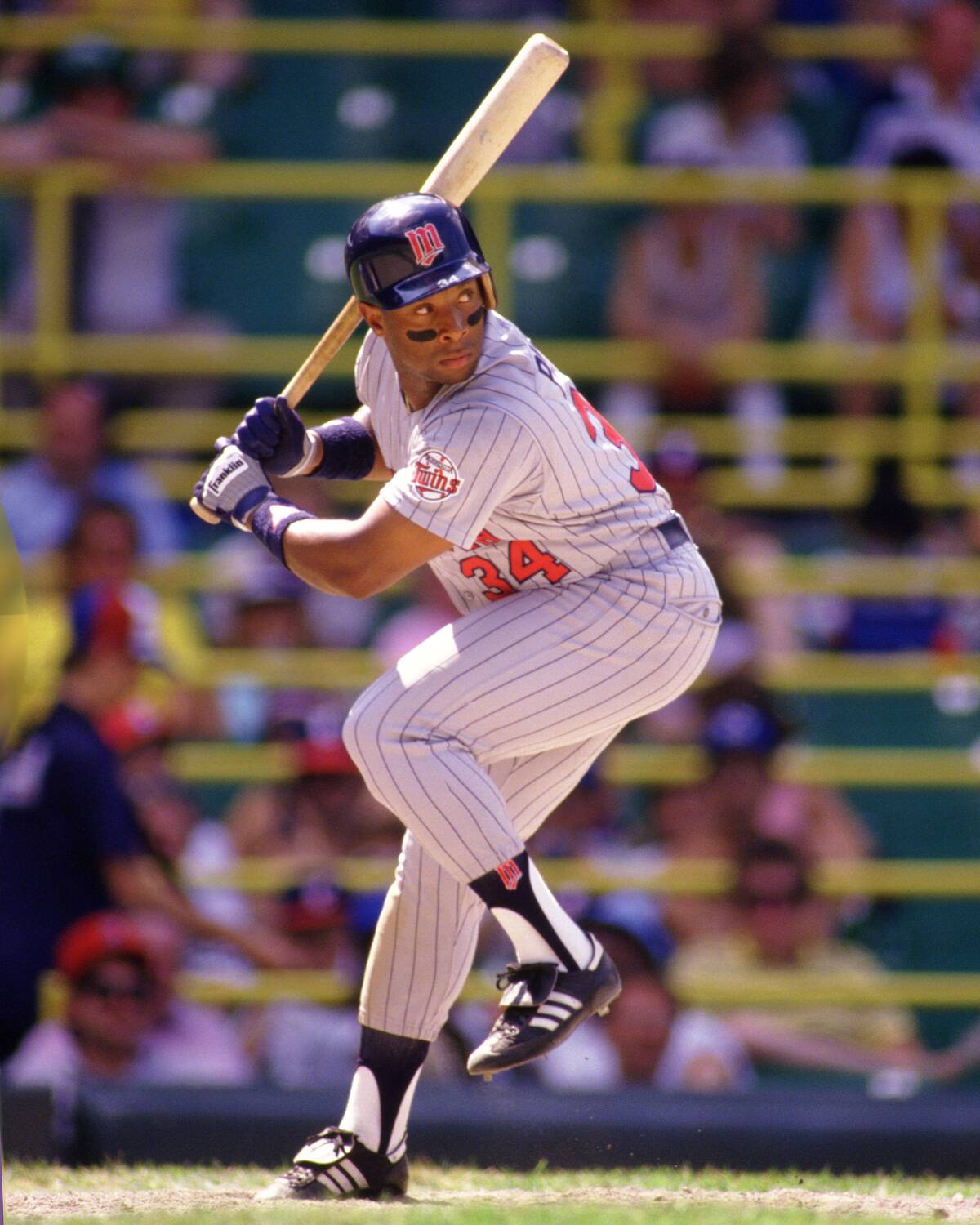

Kirby Puckett

Puckett was a dazzling star for the ’80s and ’90s Minnesota Twins before vision loss prematurely ended his career after 11 seasons. Had he played for 15 or 20 years, it’s likely that his numbers would have made him a lock — but his career WAR of 51 puts him just on the cusp of Cooperstown.

Off-field issues, including misconduct allegations, muddied Puckett’s legacy post-retirement, while statistical analysis shows that Puckett had a brief prime compared to some of his contemporaries. His 2001 induction into the Hall was likely spurred by his tragic retirement and status as a Minnesota Twins icon.

Gaylord Perry

It’s said that 300 career wins makes a pitcher a lock for Cooperstown, and Gaylord Perry won 314 games during his career. However, it look Perry 22 seasons to achieve this feat, and he also lost 265 games along the way. While he won two Cy Young awards, he never pitched for a particularly competitive team.

There’s also the fact that Perry is perhaps most famous for using spitballs and other substances to doctor baseballs. While he somehow became a beloved figure for this, it’s somewhat discordant that the Hall of Fame would reward an admitted cheater.

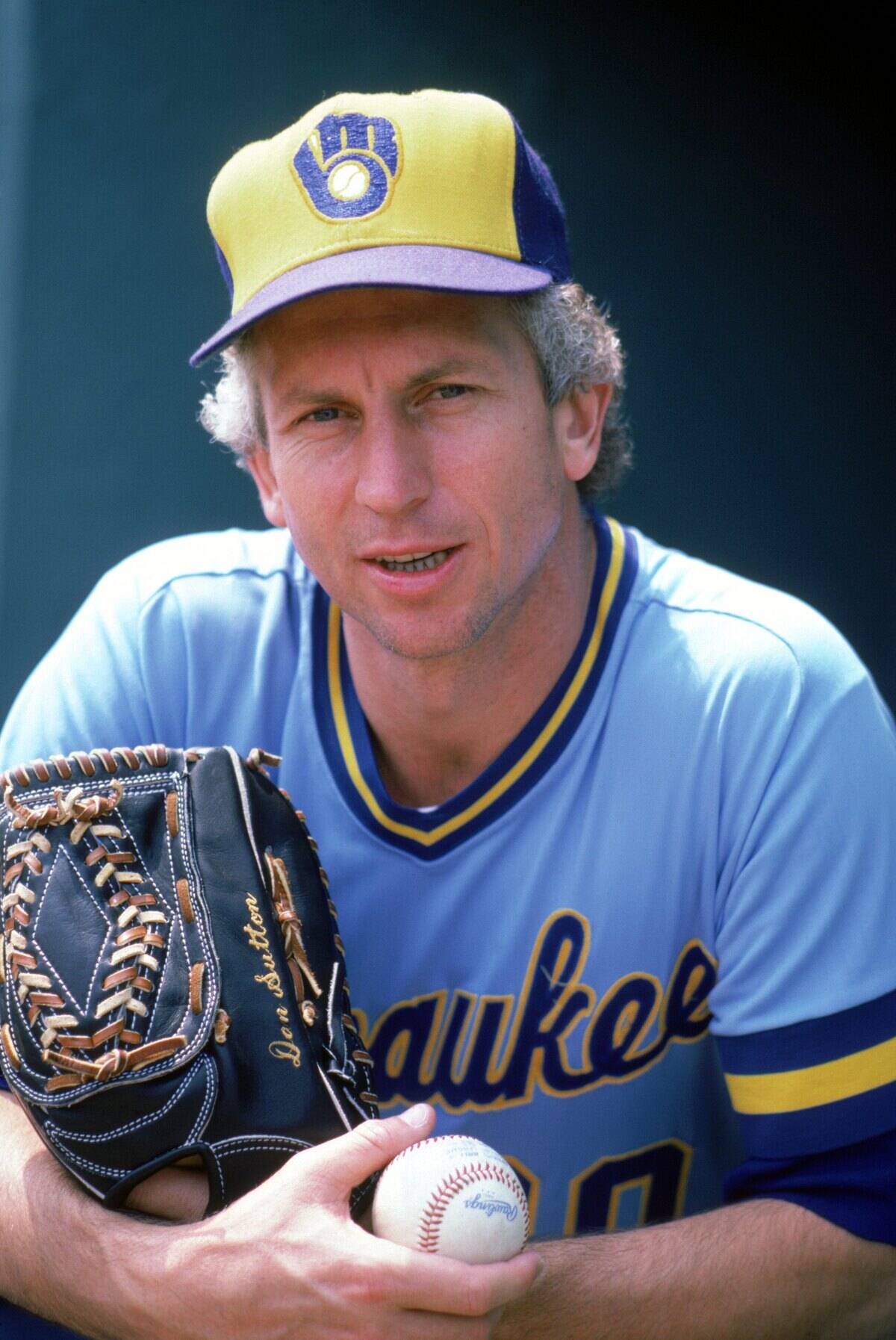

Don Sutton

Don Sutton established himself as a dependable pitcher whose career seemingly would never end. After 23 seasons and 324 wins, though, Sutton did indeed hang up his cleats with career metrics that placed him at the cusp of the Hall of Fame.

He was inducted into the Hall in 1999, more than a decade after his retirement. While most felt that he deserved the honor, it was more a matter of voters rewarding consistent service rather than peak performance. Sutton never led the league in ERA or strikeouts. While he was a steady hand, he was not a star.