Early Color Photos That Look Like They Were Taken Yesterday

We tend to think of color photography as a relatively recent development. After all, coverage of most events prior to the 1960s or so was done using black and white photography.

But that doesn’t mean that color photography didn’t exist earlier in the 20th century. In fact, the principles behind this technology were well known as early as the 19th century, but the process of creating a viable color photograph was so involved that most photographers simply chose to capture images in black and white. Let’s explore some remarkable color photographs that are all over a century old.

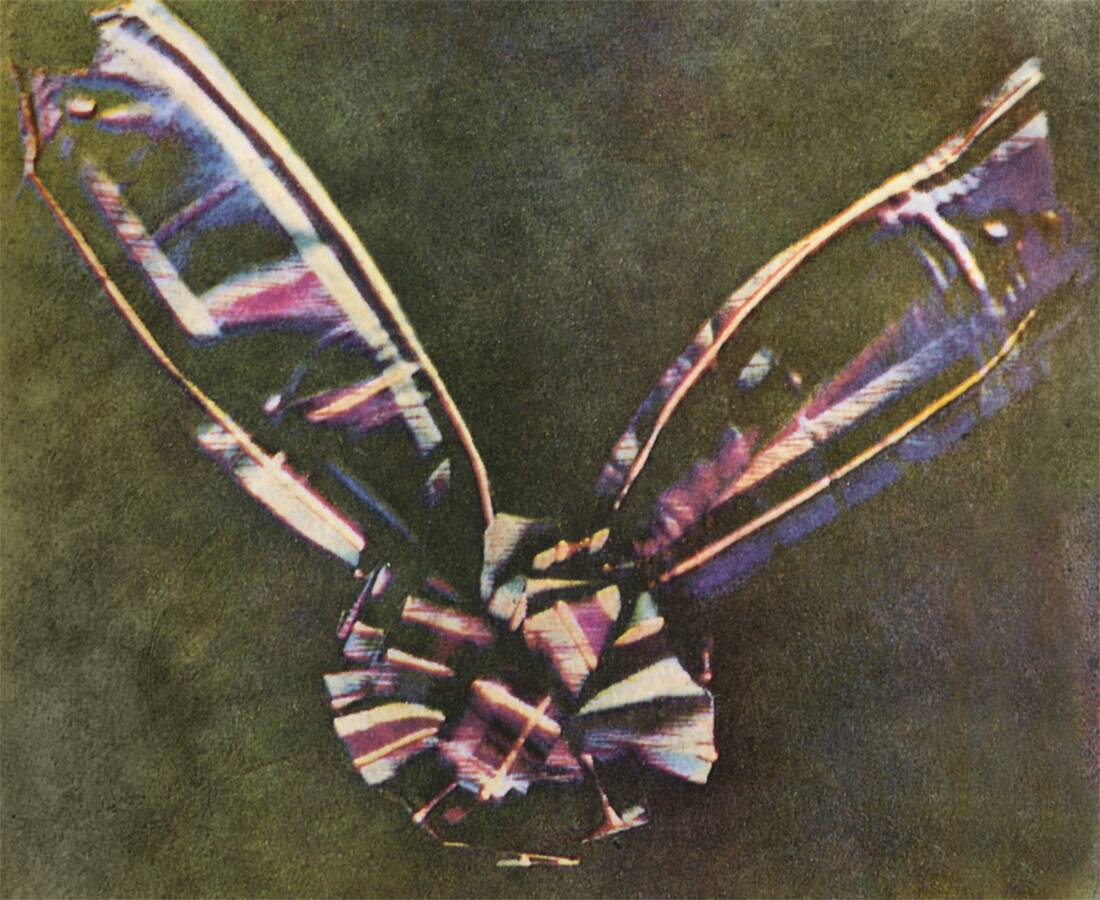

This is one of the earliest color photographs.

This image shows a tartan ribbon and was captured by Scottish physicist James Clerk Maxwell in 1855. It’s quite possible that this is the earliest undoctored color photograph on record, as earlier specimens were likely touched up and hand colored.

Maxwell was able to create this image using the three-color method — which can create any color through blending red, green, and blue images. By capturing the same image through three different tints and then overlaying them on top of each other, a color photograph is the result.

Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky was a photography pioneer.

This image of Russian photographer Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky appears in vivid, accurate color, with an impressive degree of clarity. These attributes make it somewhat shocking, then, that this photograph was snapped in 1912.

The quality of the photograph — created using the same principles of three-image color photography — is proof positive that Prokudin-Gorsky was a pioneer in this field.

Around 1905, he began an ambitious project.

Prokudin-Gorsky began researching the science of photography in the late 19th century and established his first photographic studio in St. Petersburg in 1901. In 1902, he met with German photographer Adolf Miethe to learn about the science of color photography.

A couple of years later, he embarked on a plan to systematically document as much of the Russian Empire as possible using color photography.

He did it all without a permanent studio.

Part of what makes Prokudin-Gorsky’s work so impressive has nothing to do with the visual clarity, and everything to do with the conditions he was working under.

Unlike most other photographers of the era, Prokudin-Gorsky was conducting this work in the field. Without access to a proper darkroom, he used a specially equipped space on a railroad car to create his photos while working in the Russian hinterland.

His photographs offer a vivid look at early 20th century Russia.

This photo was taken in modern-day Uzbekistan and shows a zindan — the name for a traditional Central Asian prison — with prisoners as well as a guard.

As most of these photographs were taken far away from Russia’s main population centers of Moscow and St. Petersburg, it’s likely that this was the first time many of Prokudin-Gorsky’s subjects had ever seen a camera.

He had some help from the Tsar.

While Prokudin-Gorsky deserves credit for the quality of his photographs, this ambitious project would not have been possible without the cooperation and support of Russian Tsar Nicholas II.

The Tsar gave the photographer permits to grant him access to restricted areas throughout the Empire, along with cooperation from the various bureaucrats and local officials he would encounter along the way.

He travelled far and wide.

This image shows a group of young peasant women as they stand in front of their traditional wooden house. It was taken in the small town of Kirillov, a rural region in northwestern Russia.

While many of the areas that Prokudin-Gorsky photographed were rural in the early 20th century and remain rural today, they offer a fascinating glimpse of customs and wardrobes that simply don’t exist anymore.

He took thousands of photographs.

Subjects of Prokudin-Gorsky’s photographs ran the gamut from groups of local people to interesting local architecture, with a particular focus on churches.

While the photographer was able to develop many of his photos in the field using his specially-designed railroad car darkroom, he took far too many pictures to develop them all. It’s estimated that he accumulated around 3,500 negatives from his time documenting the Russian Empire between 1909 and 1915.

Russia was in flux at the time.

Pastoral images like this one, showing farm workers taking a break from haying, have a timeless quality to them. But while many of these scenes had been virtually unchanged from centuries prior, big changes were in the air.

Prokudin-Gorsky’s documentation of the Russian Empire came during a calm before several storms. World War I broke out towards the tail end of his project, while the Russian Civil War — and the eventual overthrow of the Tsar — was just a few years away.

His photos show remarkable fidelity.

Many black and white photos of the early 20th century offer similar vantage points of cities and towns, but in most cases, it’s tough to make the details out.

This image of Perm, Russia shows incredible clarity, to the point that virtually every individual building can be identified. Modern-day Perm has around a million inhabitants, but in the early 20th century, it was a much smaller city.

The photos document an ambitious empire.

This image of a modern-looking rail bridge over the Kama River near Perm shows the increasing interconnectedness of the vast Russian Empire. At the time, the Tsar was making efforts to stitch together remote outposts using modern infrastructure.

While the reign of the Tsars would not last for much longer, this same blueprint would be followed throughout the 20th century as Russia — and later, the Soviet Union — became the largest country by land area on the planet.

His project spanned six years.

The Nilov Monastery, seen here, is located on Stolobny Island in Lake Seliger and was originally founded in 1594. Unlike some of Prokudin-Gorsky’s other subjects, the monastery hasn’t changed much over the years.

While the monastery itself looks much the same as it does in the modern era, it’s still striking to consider that this photograph was taken in 1910 and is undoctored. Black and white photographs can be colorized, but they don’t offer true colors like the ones seen here.

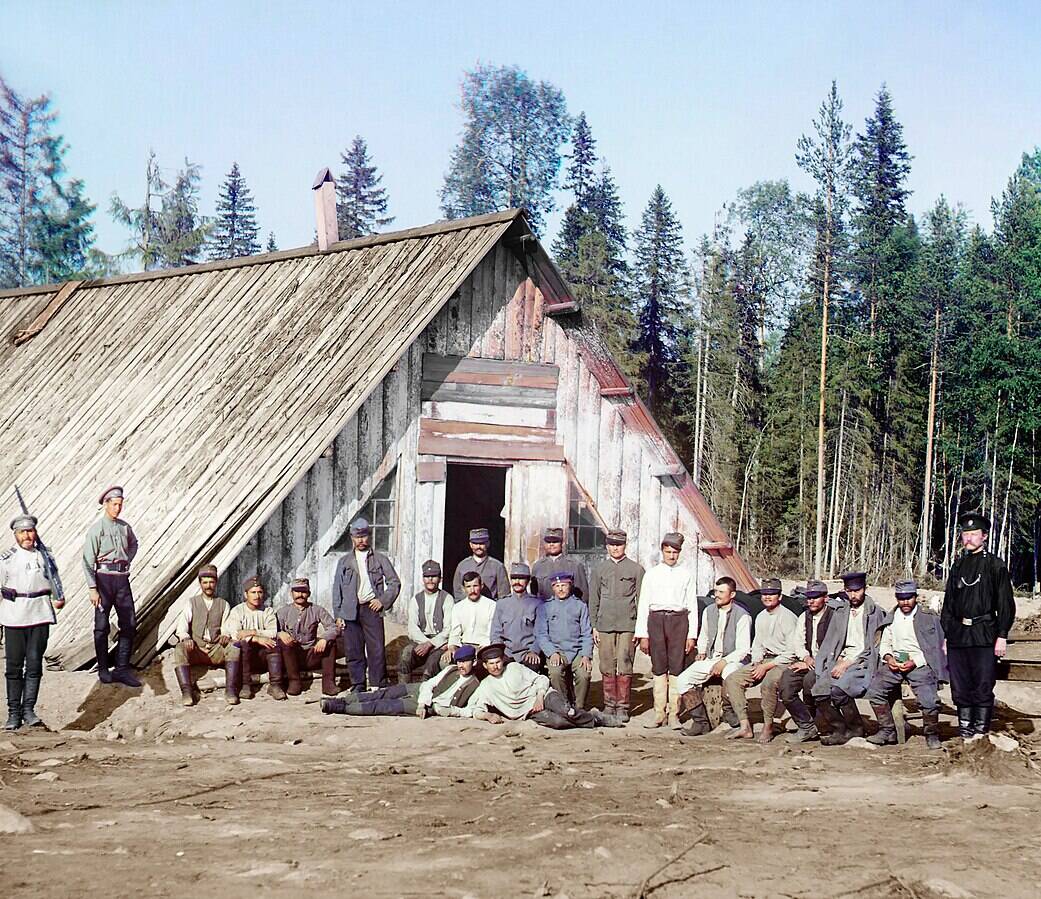

The project ended unceremoniously.

This photograph of Austrian prisoners of war in Olonets Provence shows that, by the end of the six-year project, World War I had broken out and parts of Russia were already changing.

In 1915, Prokudin-Gorsky concluded his work. It’s estimated that about half of his 3,500 negatives and photographs were immediately confiscated by Russian authorities when he returned to St. Petersburg, as they contained strategically sensitive images that might hinder Russia’s war effort.

Many photographs were lost.

Prokudin-Gorsky said that most of the confiscated photos weren’t of much interest to the general public. In addition to the confiscations, some photos were given away and others were hidden, which means that there may be some photos or negatives that have yet to be rediscovered.

Ultimately, Prokudin-Gorsky’s remarkable photographs were largely forgotten for decades owing to political instability in Russia.

The photos were stored in a basement in Paris.

Because Prokudin-Gorsky’s benefactor was the Tsar — who was later executed during the Russian Civil War — his photographic project was forgotten for many years, with these photos stored in a Parisian basement for safekeeping.

In 1948, the United States Library of Congress purchased the collection from his heirs, and in the following decades, they developed the negatives and publicized the photos for all to see.