The Bizarre Connection Between Charles Manson And The Beach Boys

On the surface, it seems like the Beach Boys and Charles Manson were polar opposites. After all, the Beach Boys were known for their surf-inspired rock music, while Manson was a notorious cult leader whose followers were responsible for some of the most notorious murders of the late ’60s.

However, beyond the surface, common strands start to emerge. Both Manson and the Beach Boys were California fixtures during the ’60s, and Manson, as a struggling musician, wanted to make inroads in the music industry — and, thanks to Beach Boys drummer Dennis Wilson, he was able to do just that.

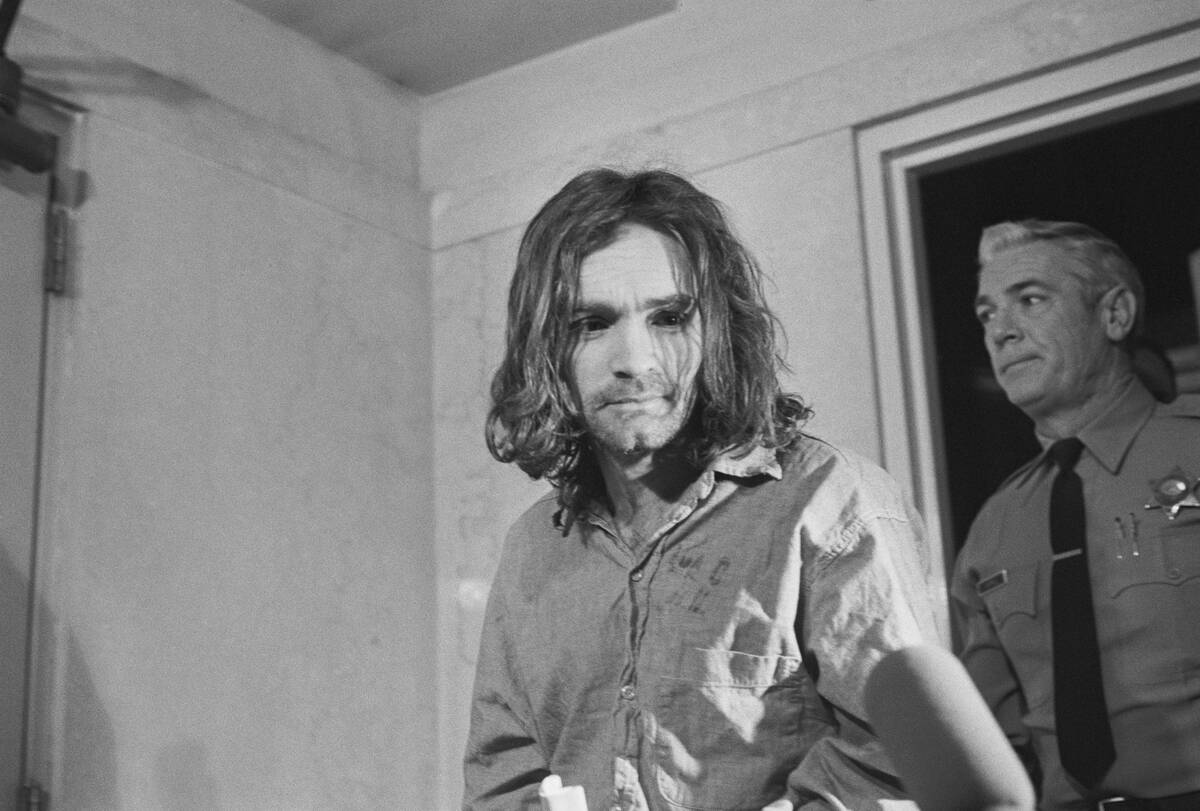

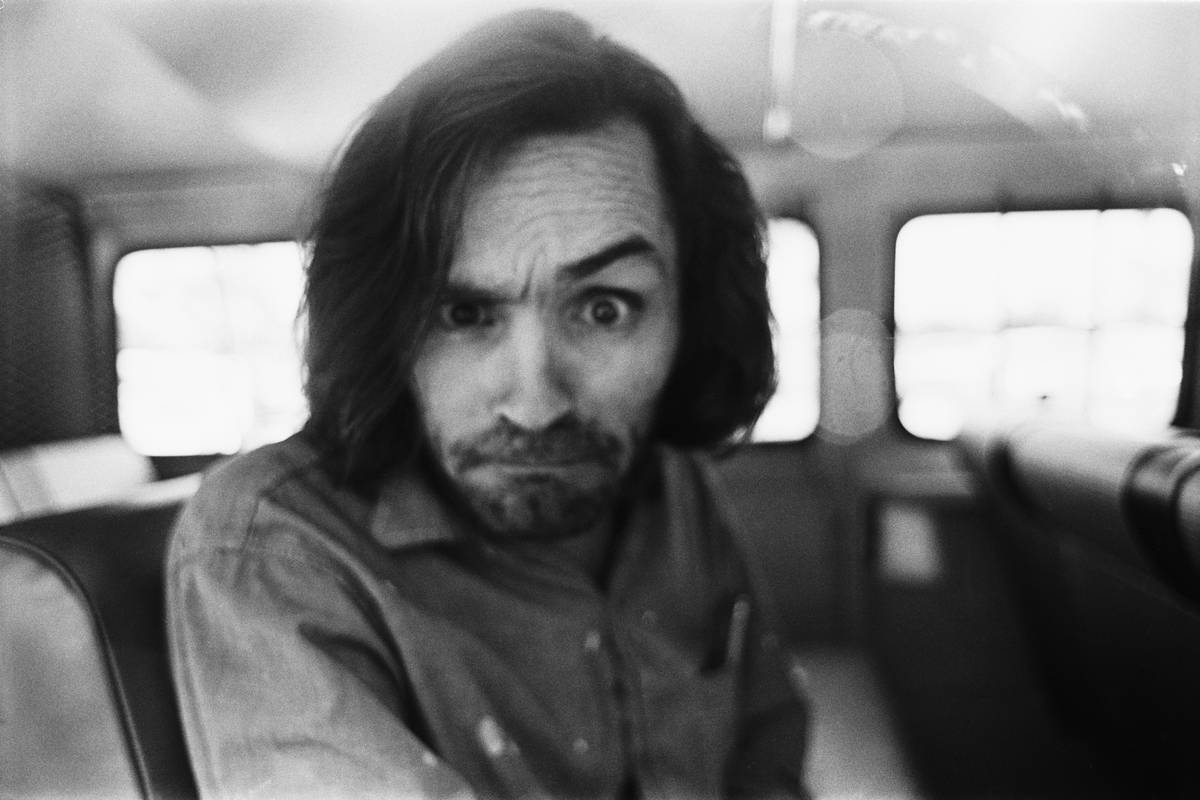

Who was Charles Manson?

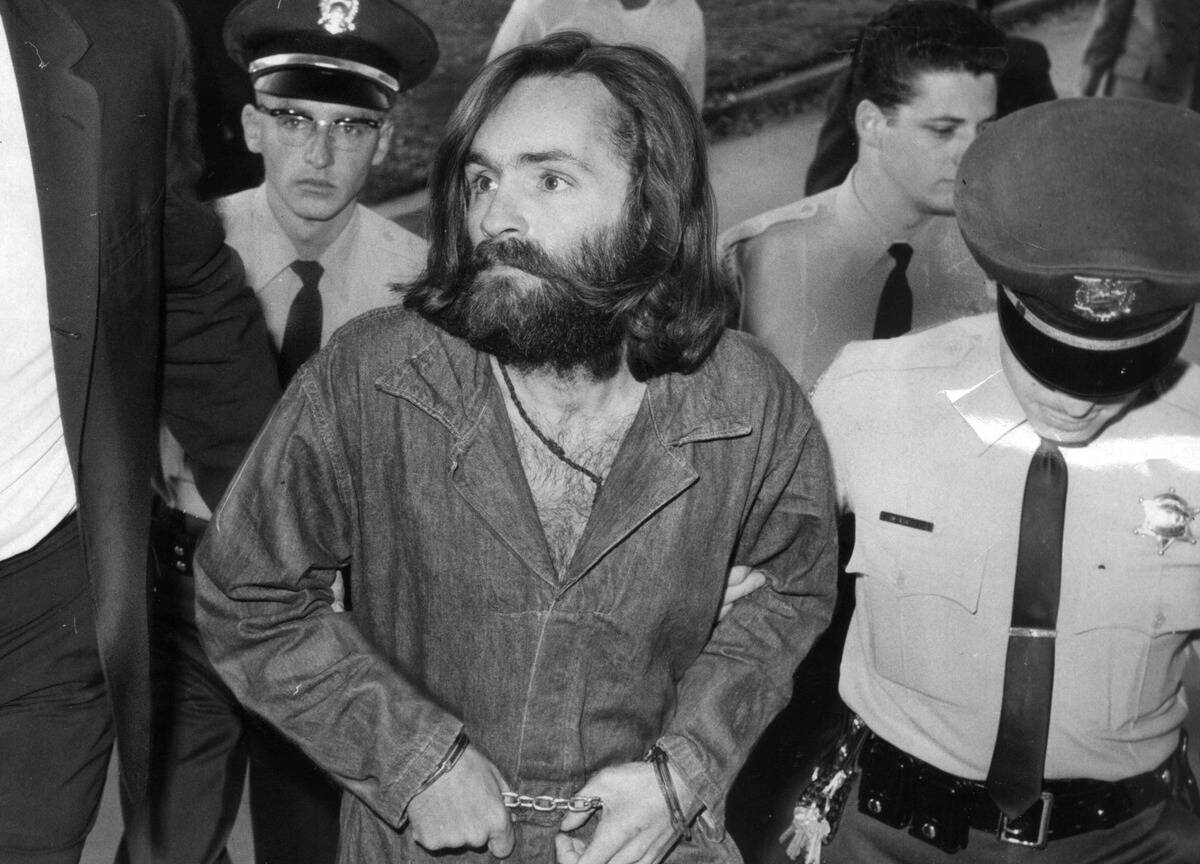

Virtually everyone knows the broad strokes of Charles Manson’s notoriety, but here’s a recap: Manson was a career criminal and musician who emerged in San Francisco during the mid-’60s to form a kind of hippie cult.

After moving with his followers to Los Angeles, members of the cult committed a series of at least nine murders in Southern California. Manson was eventually convicted, and spent the rest of his life in prison. He died in 2017 at the age of 83.

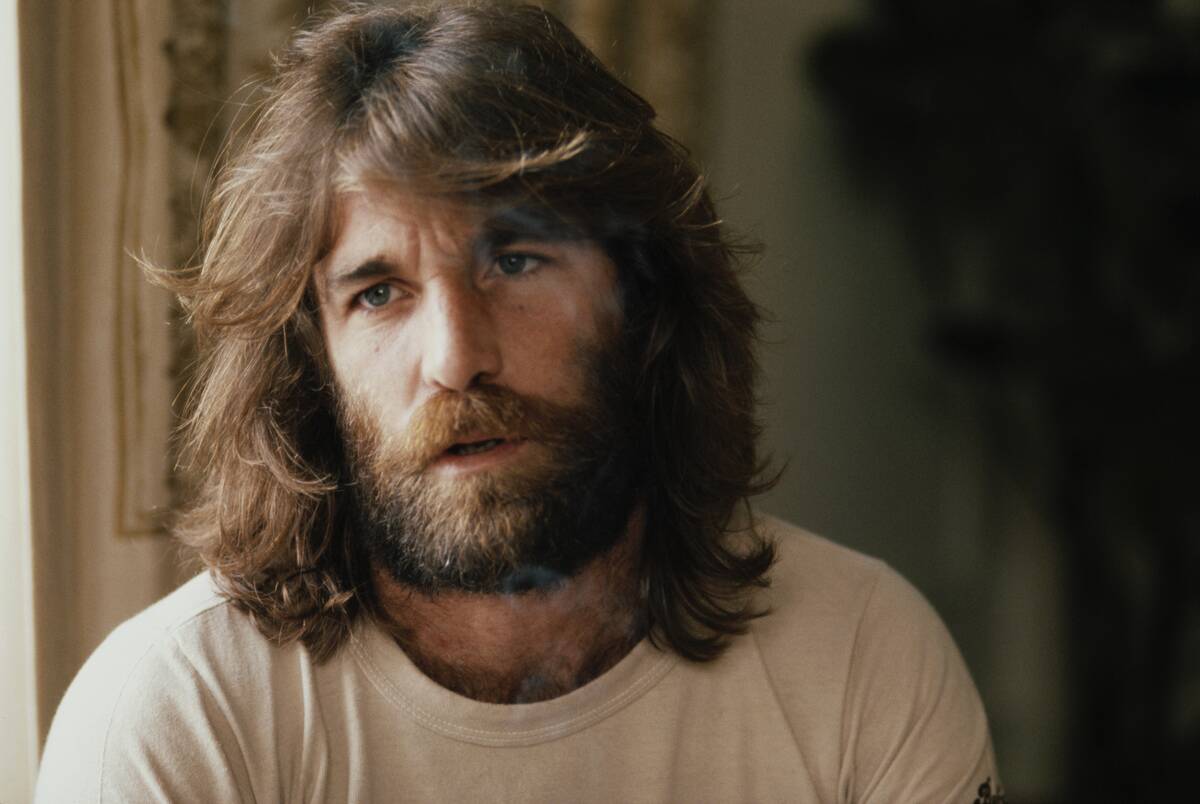

Who were the Beach Boys?

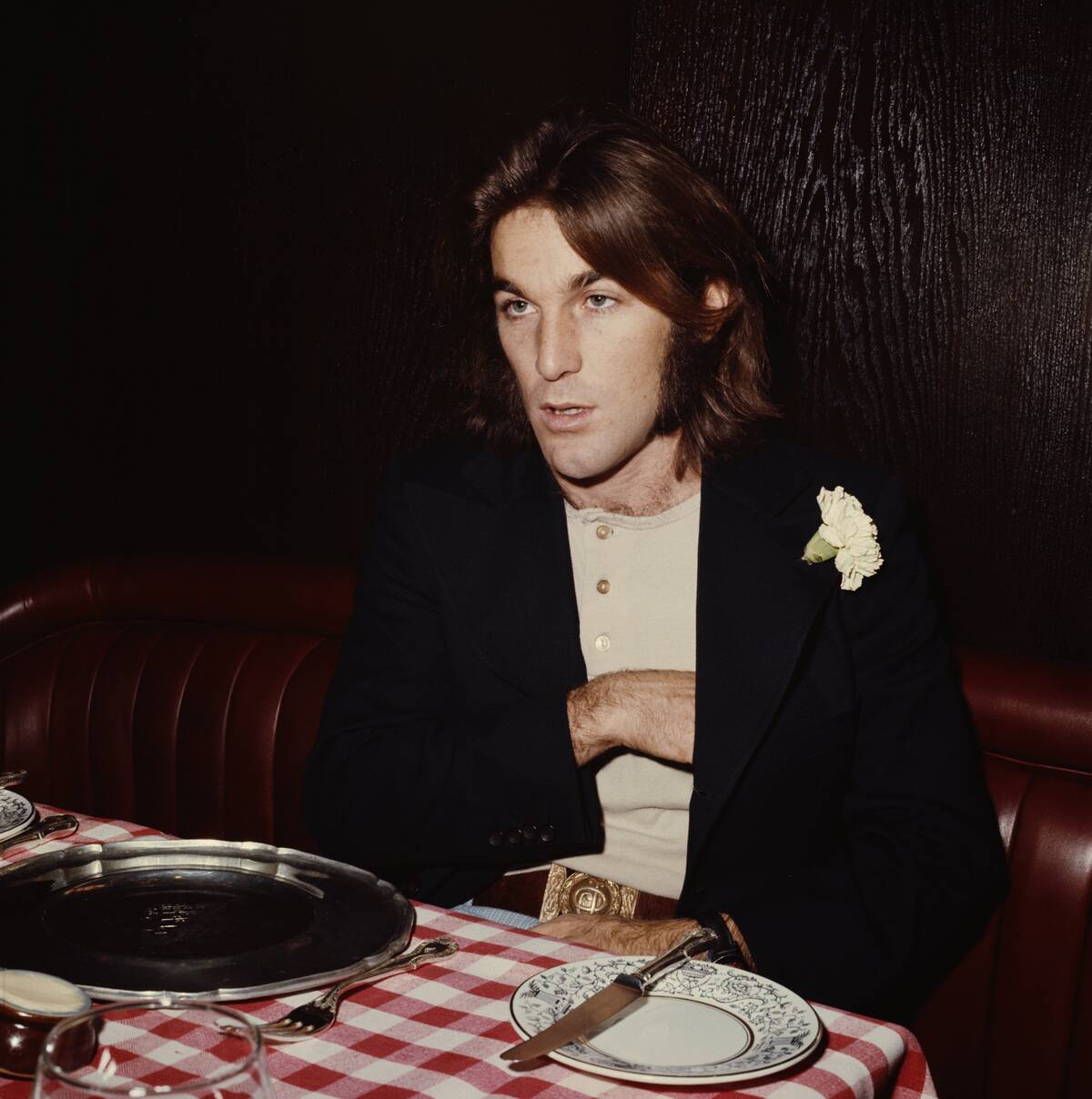

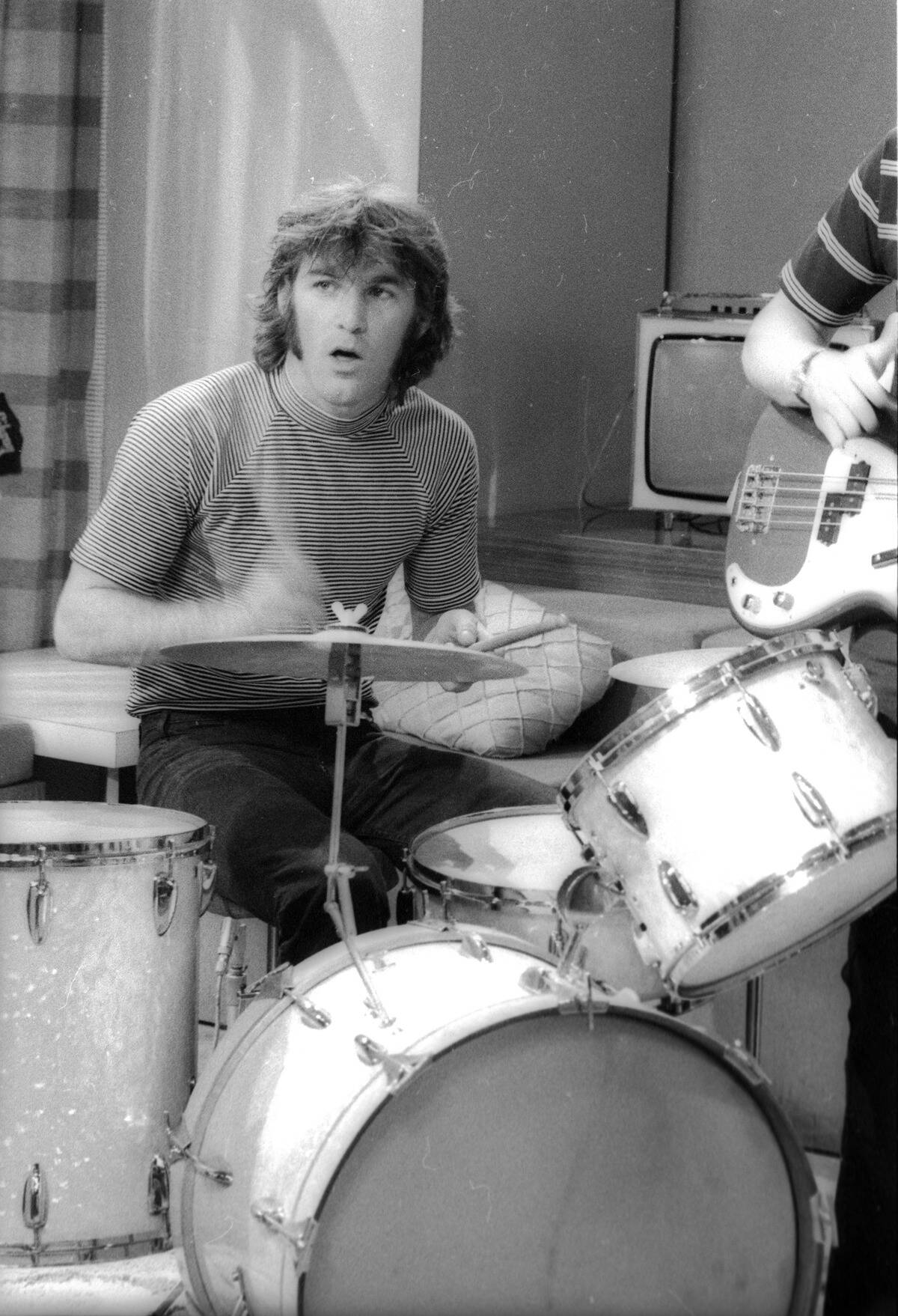

The Beach Boys, in their original incarnation, consisted of brothers Brian, Dennis, and Carl Wilson, along with their cousin Mike Love and their friend Al Jardine. The group became a fixture of ’60s rock music, releasing a series of hits inspired by surfing and car culture.

Towards the tail end of the decade, the Beach Boys explored new musical directions. While Pet Sounds is regarded as one of the best albums of all time, internal tensions had left the individual members of the group feeling somewhat adrift by the late ’60s.

In 1968, a chance encounter changed everything.

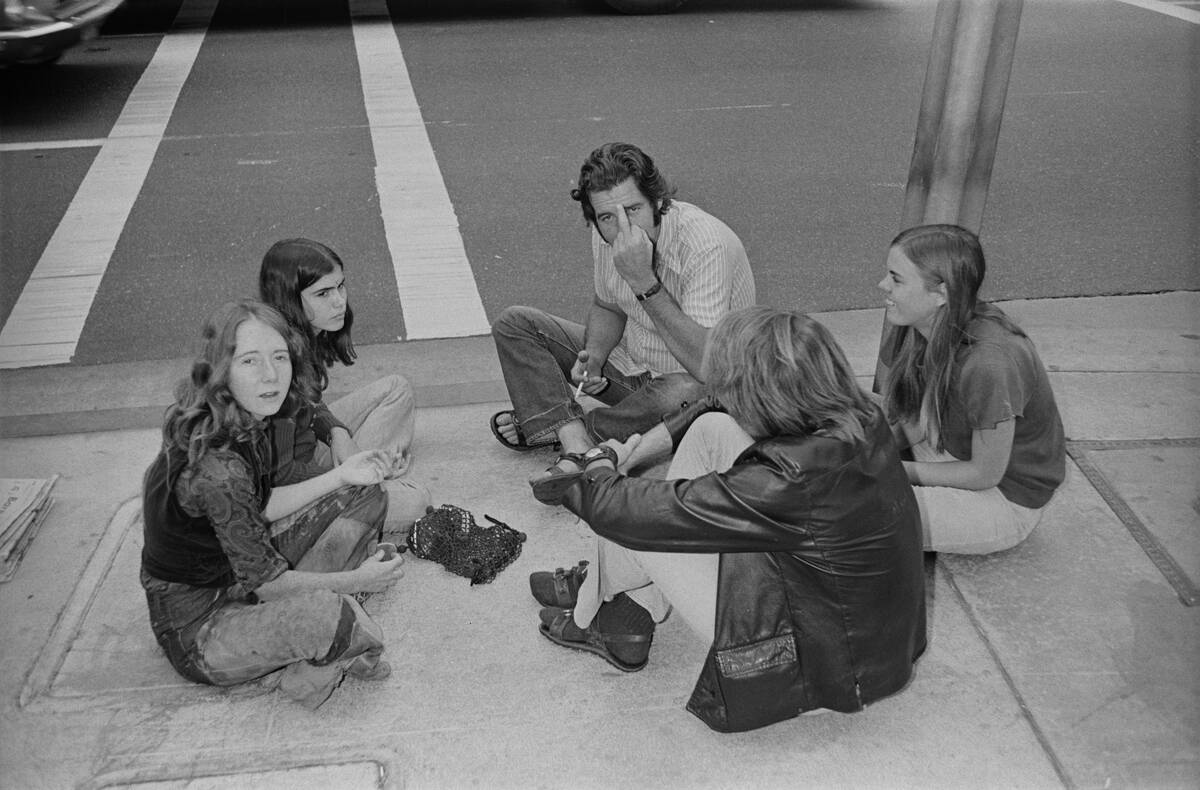

Manson had moved his followers to Los Angeles with an eye to starting up a career as a musician, and a chance encounter immediately gave him access to one of the biggest musicians of the day.

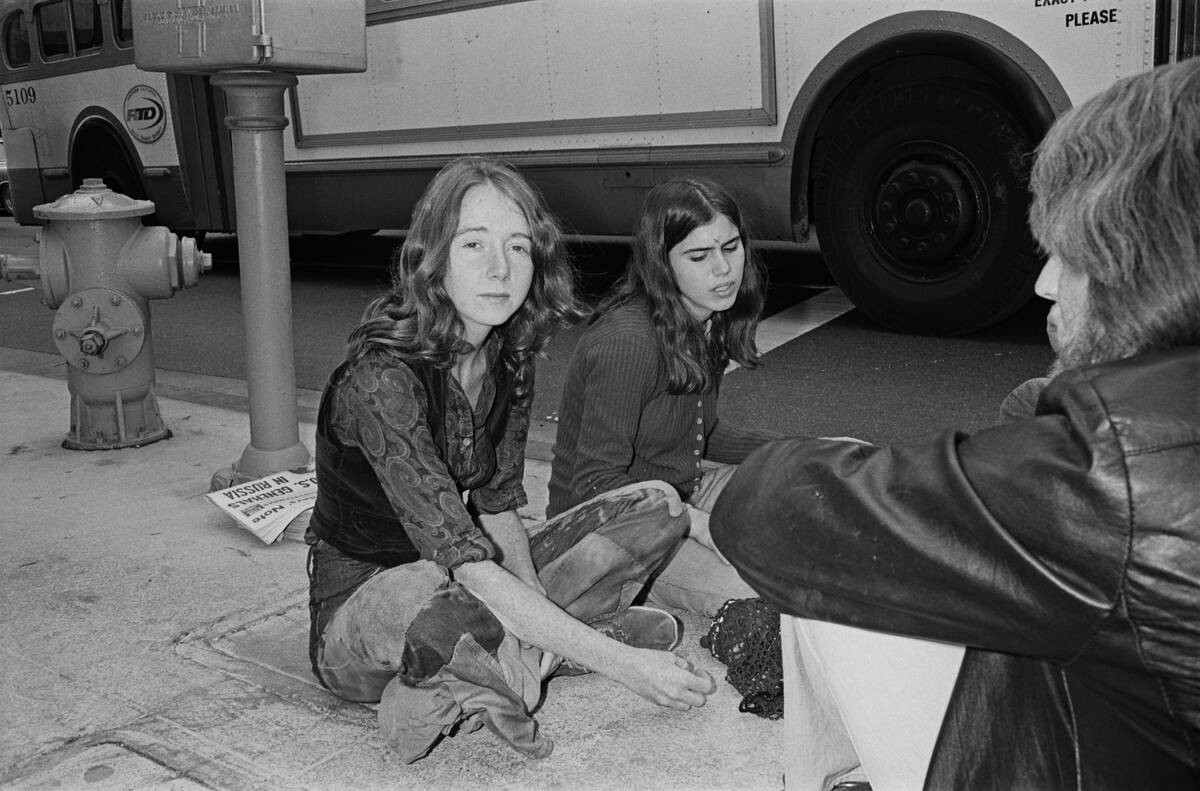

In the summer of 1968, Beach Boys drummer Dennis Wilson was driving in southern California when he saw and picked up two female hitchhikers. As it turns out, both women were members of Manson’s cult, which he called his “family.” Wilson drove the two women to their destination.

A week later, Wilson saw the hitchhikers again.

This time, Wilson took the women to his home at 14400 Sunset Boulevard. Once there, they told him about their “guru,” a guy named Charlie. After hanging out for a while, Wilson had to leave to go to a recording session.

When Wilson returned home later that night, he found that the women were still there — along with about a dozen other people, including Charles Manson himself. By all accounts, Wilson and Manson hit it off immediately.

Wilson allowed them to move in.

In keeping with the free love ethos of the era, Wilson decided to let the Manson family move in to his mansion. Wilson spent around $100,000 (about $900,000 in modern dollars) on the family, with most of this spent on cars, food, clothes, and penicillin to treat persistent gonorrhoea infections.

For his part, Wilson was happy with the arrangement. He could easily afford to pay the funds, had more than enough space for everyone, and appreciated the female company. In a magazine article written during the time, he boasted about living with 17 women.

The two became musical collaborators.

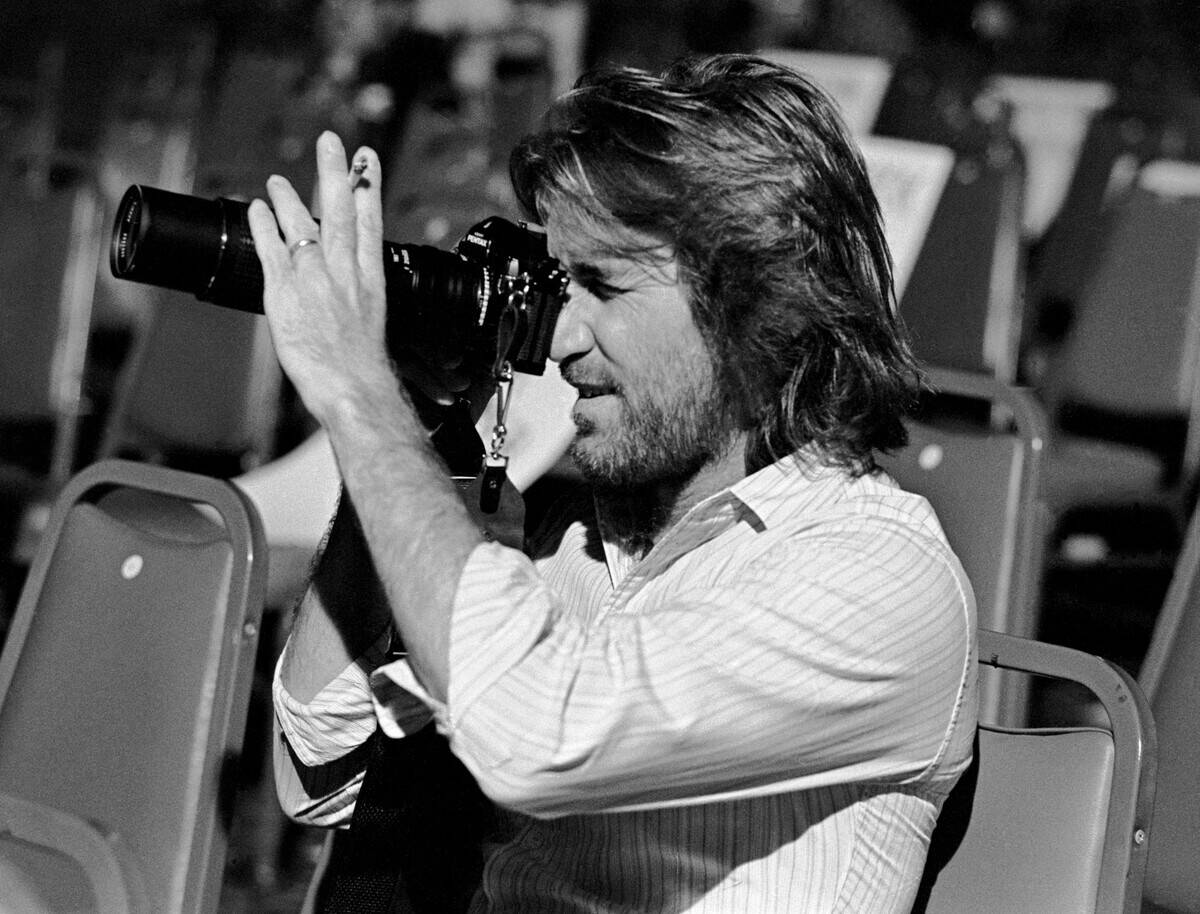

Wilson said in a 1968 interview that when he met Manson, “I found he had great musical ideas. We’re writing together now. He’s dumb, in some ways, but I accept his approach and have learned from him.”

Their collaboration went further when Wilson introduced Manson to some of his friends in the music business, most notably record producer Terry Melcher.

Manson even wrote a Beach Boys song.

Dennis Wilson recorded one of Manson’s songs in September of 1968 — originally titled “Cease to Exist,” but later renamed “Never Learn Not to Love.”

The reworked song was released as a single B-side the following year, with Wilson listed as the sole songwriter. By this point, Manson was not in a position to challenge this, and Wilson said that he’d bought the publishing rights in exchange for “about a hundred thousand dollars’ worth of stuff.”

Things became increasingly chaotic.

In time, Wilson became less enamoured with the hippies crashing at his mansion. The unpredictable Manson family destroyed several of Wilson’s cars, and Manson’s outbursts left Wilson feeling uneasy.

Eventually, a fearful and conflict-averse Wilson chose to simply leave. He moved in with his friend Gregg Jakobson in Santa Monica. The Manson family stayed at Wilson’s home, stealing or destroying virtually all of his possessions in the process.

Three weeks later, the Manson Family was evicted.

Dennis Wilson was seemingly free of the Manson Family, but this wouldn’t last. Manson was eager to maintain ties to Wilson (and the music industry at large), and he sought to re-establish contact by sending Wilson a bullet with a threatening message.

While many who were there maintain that Wilson was intimidated by Manson, Beach Boys collaborator Van Dyke Parks claimed that Wilson responded to the threat by beating up Manson — though he did acknowledge that this was just something he heard.

In 2016, Mike Love revealed something troubling.

Beach Boys member Mike Love stated in his 2016 memoir that Dennis Wilson was indeed afraid of Manson, and for good reason — as Love wrote, Wilson said he’d seen Manson shoot a man “in half” using an M16 rifle, then hid the body inside a wall.

To add to this, Terry Melcher went on the record as saying that Wilson became aware that the Manson Family “were killing people,” which led Wilson to become “so freaked out he just didn’t want to live anymore.”

In August of 1969, the Manson Family murders took place.

On August 8, 1969, Manson Family members killed five people at the home of actress Sharon Tate — and then, the following night, they killed two more people. The vicious murders attracted immediate media attention.

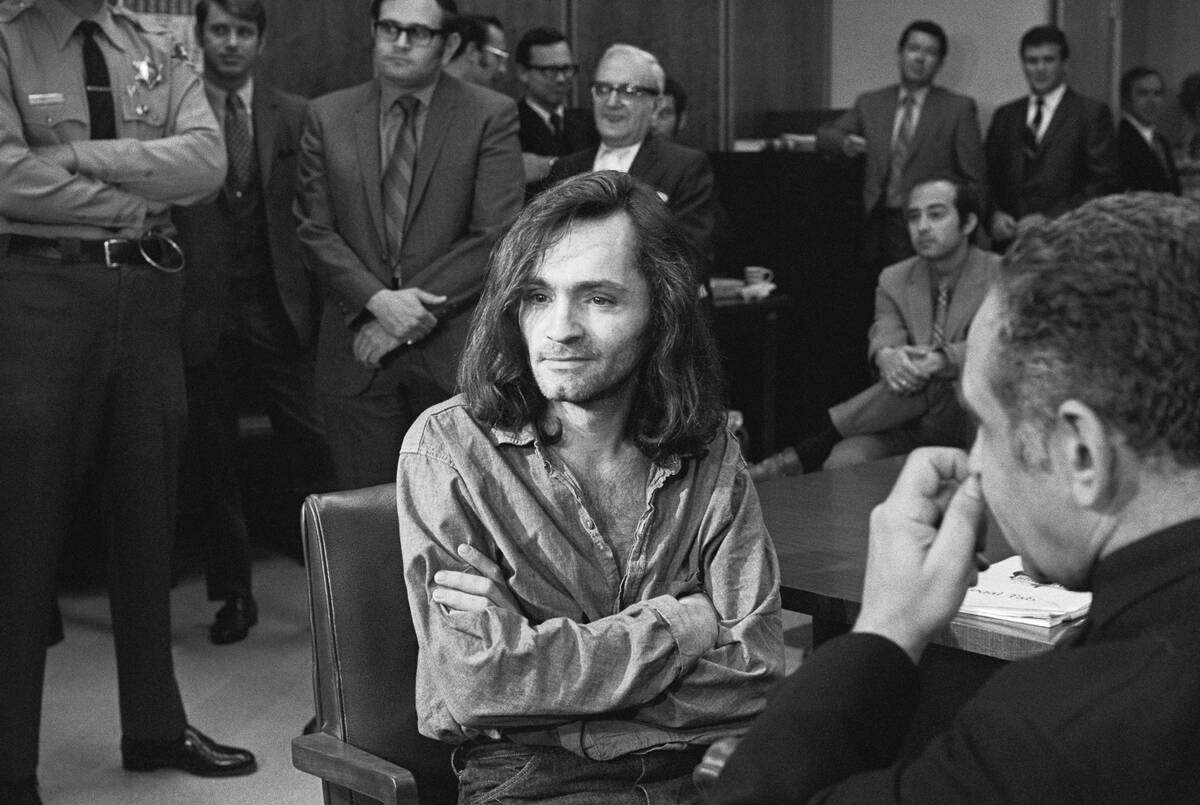

Shortly after the murders, and before Family members were suspected, Manson visited Wilson to say that he’d “just been to the moon,” and demanded money from Wilson — a demand that a nervous Wilson immediately agreed to.

In time, Manson and his Family members were convicted.

Wilson’s close collaboration with Charles Manson just a year before the notorious murders meant that he had some insights into the inner workings of the Family — but Wilson was too scared to testify publicly against Manson.

Prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi instead interviewed Wilson in private. Terry Melcher later said that prosecutors “thought [Wilson] was nuts, and by that time, he was. He had a hard time separating reality from fantasy.”

The Family continued to haunt Wilson.

Even with Manson and his collaborators in prison, there were still members of the Manson Family who were free — and Wilson claimed that he received frequent death threats from these members of the Manson Family.

Wilson was also evidently haunted by his collaboration with Manson. When asked for the tapes of the songs they’d recorded together, Wilson said that he’d destroyed them because “the vibrations connected with them didn’t belong on this earth.”

Wilson never really got over it.

Whenever he was asked about Manson, Wilson maintained that he regretted any association the two had together. In a 1978 biography, Wilson cryptically said, “I know why [he] did what he did. Someday, I’ll tell the world. I’ll write a book and explain why he did it.”

Throughout the ’70s, Wilson’s life entered a spiral of self-destruction, a state that biographers and friends believe was at least partly influenced by his guilt surrounding the Manson Family.

Wilson died in 1983.

After years of substance abuse, Wilson was a shell of his former self — unable to play drums to a reasonable standard and also unable to speak normally. By early 1983, he had quit the Beach Boys, rebuffed efforts to get him into rehab, and was homeless.

On December 28, 1983, Wilson got drunk and went to a marina in an attempt to recover belongings that had been thrown overboard from his yacht years earlier. He drowned in his attempts and was buried at sea. In a statement, the Beach Boys said, “His spirit will remain in our music.”