The Groundbreaking, Tragic Life Of Lenny Bruce

The modern world of comedy — one in which comedians are largely free to push boundaries and offend in the name of artistic expression — owes Lenny Bruce a debt of gratitude.

That’s because the comedy landscape in the middle of the 20th century was vastly different, with comedians constrained to a narrow range of quippy jokes. Lenny Bruce is credited with helping to shift this paradigm, even if he paid a heavy price for doing so.

He was born on Long Island.

Born Leonard Alfred Schneider in 1925, the young Lenny Bruce spent his childhood in the Long Island town of Mineola. While he rarely saw his father, his mother Sally was a major influence on his showbiz career, as she worked as a stage performer.

After his parents divorced, Bruce spent time living with various relatives. In 1942, at the age of 16, he enlisted in the United States Navy.

He pushed boundaries right from the start.

In 1945, one of Bruce’s earliest comedic performances was apparently so successful in pushing boundaries that it resulted in his dishonorable discharge from the Navy.

Bruce dressed in drag for a comedic show for his fellow sailors. After his commanding officers took exception, Bruce decided to double down and tell the ship’s medical officer that he was experiencing homosexual urges. Unsure of what to do with the young comedian, the Navy issued a dishonorable discharge.

He was a noted hustler.

With his early comedy only barely paying the bills, Bruce looked to a variety of money-making schemes and scams. He legally chartered something called the “Brother Mathias Foundation” to solicit donations for a made-up leper colony.

While the scheme was eventually uncovered, authorities weren’t able to pin enough on Bruce to earn a conviction.

His career began in fits and starts.

Going by the name Lenny Marsalle, and eventually Lenny Bruce, the comedian was given $12 and a spaghetti dinner for his first comedy show in Brooklyn in 1947.

From there, Bruce made a living writing comedic screenplays in the early ’50s. Later in the decade, he teamed up with fellow comedian Buddy Hackett for a duo known as the “Not Ready for Prime Time Players” — decades before SNL reused the name.

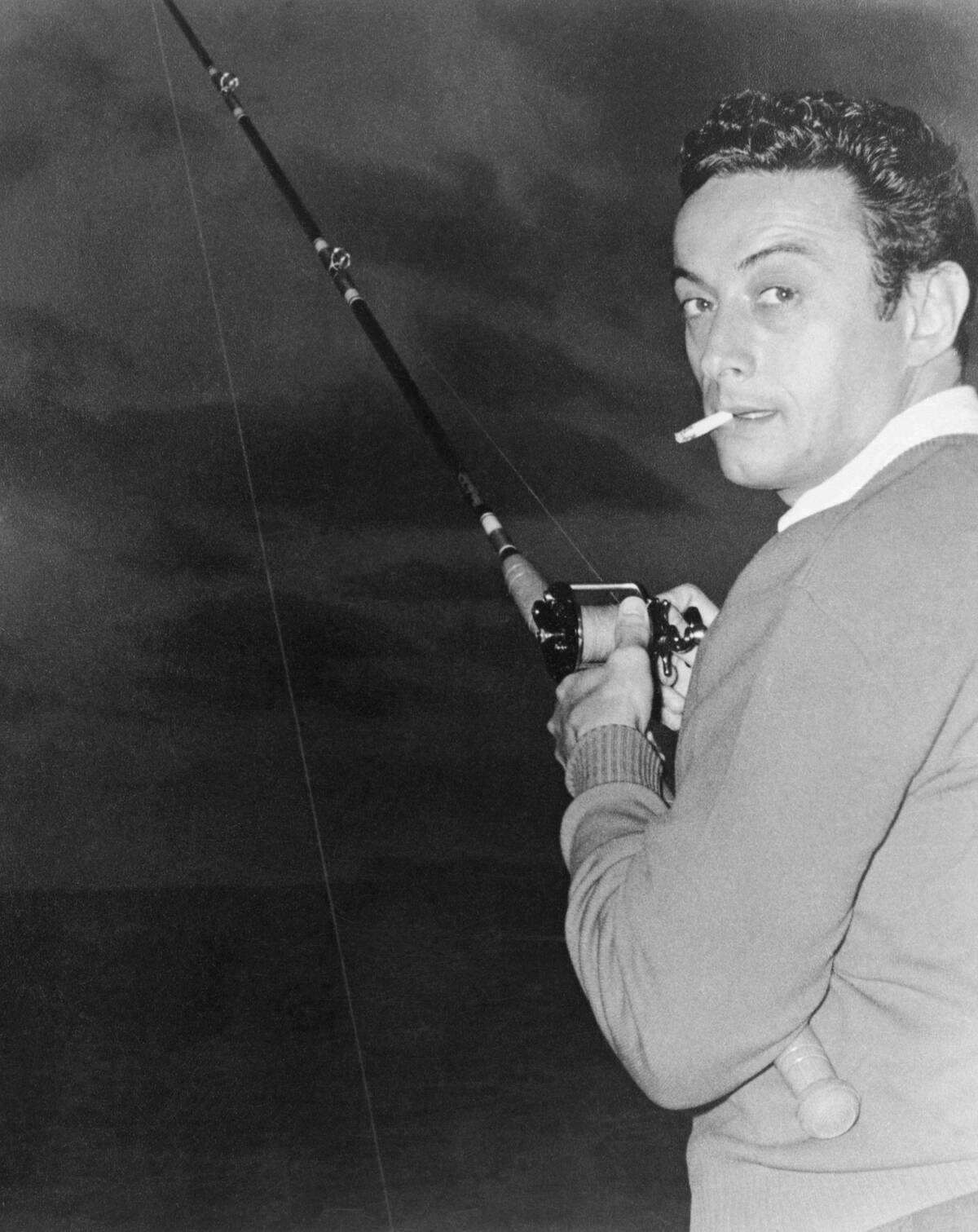

He was known for working blue.

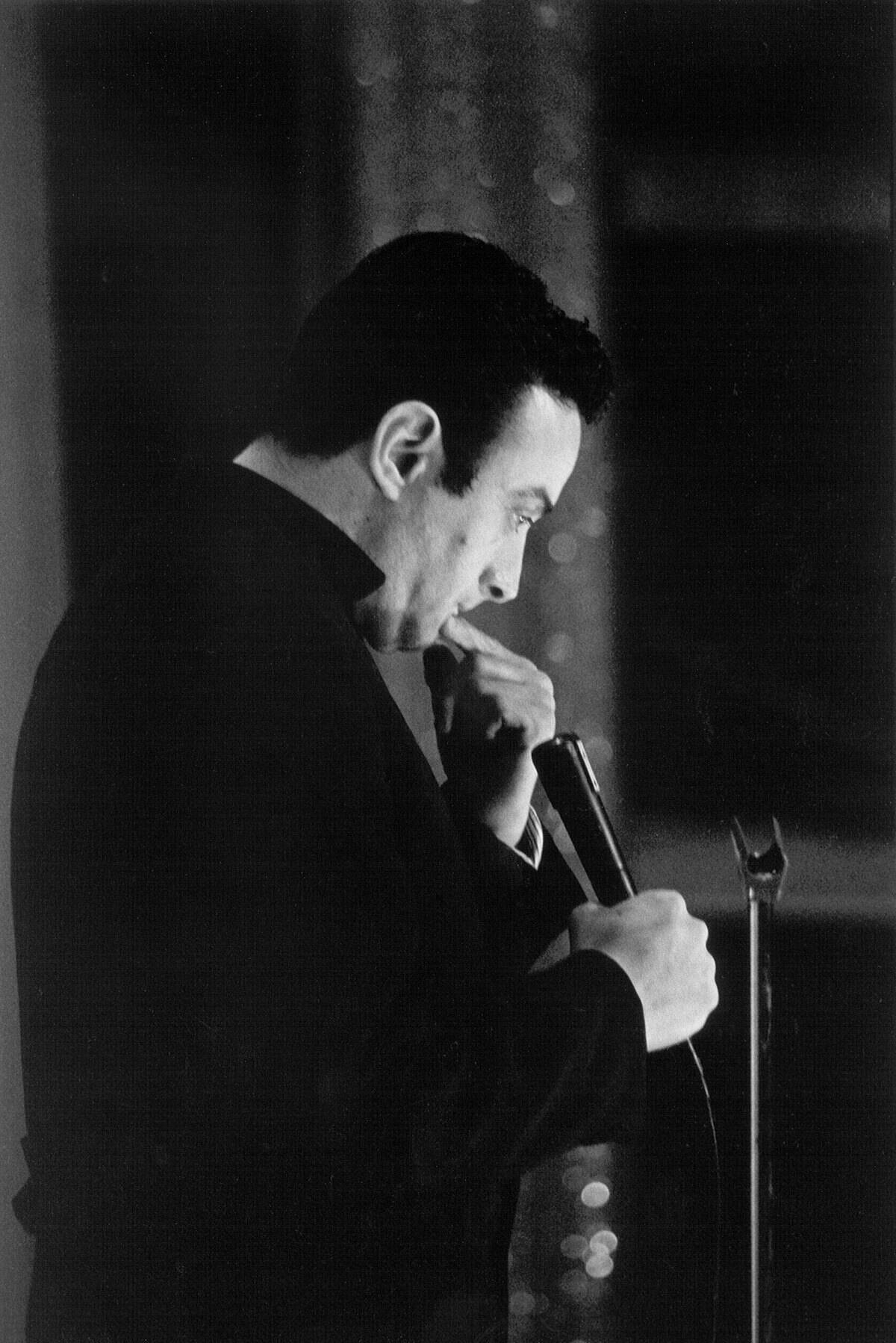

Using risqué or explicit material is known as “working blue” in comedy, and it’s in this area that Bruce excelled. He earned a following and released several albums of his genre-pushing comedy.

However, his profane material limited his audience significantly, as most television shows wouldn’t run the risk of booking a comedian who was known to be offensive.

In 1961, his comedy got him arrested.

During an October 1961 show at San Francisco’s Jazz Workshop, Bruce used a vulgar term and doubled down by explaining how the meaning of the word can change in different contexts.

This was a watershed moment for Bruce and for comedy as a whole. While he was eventually acquitted by a jury, the incident branded him as a troublemaker — a reputation that would haunt him for the rest of his life.

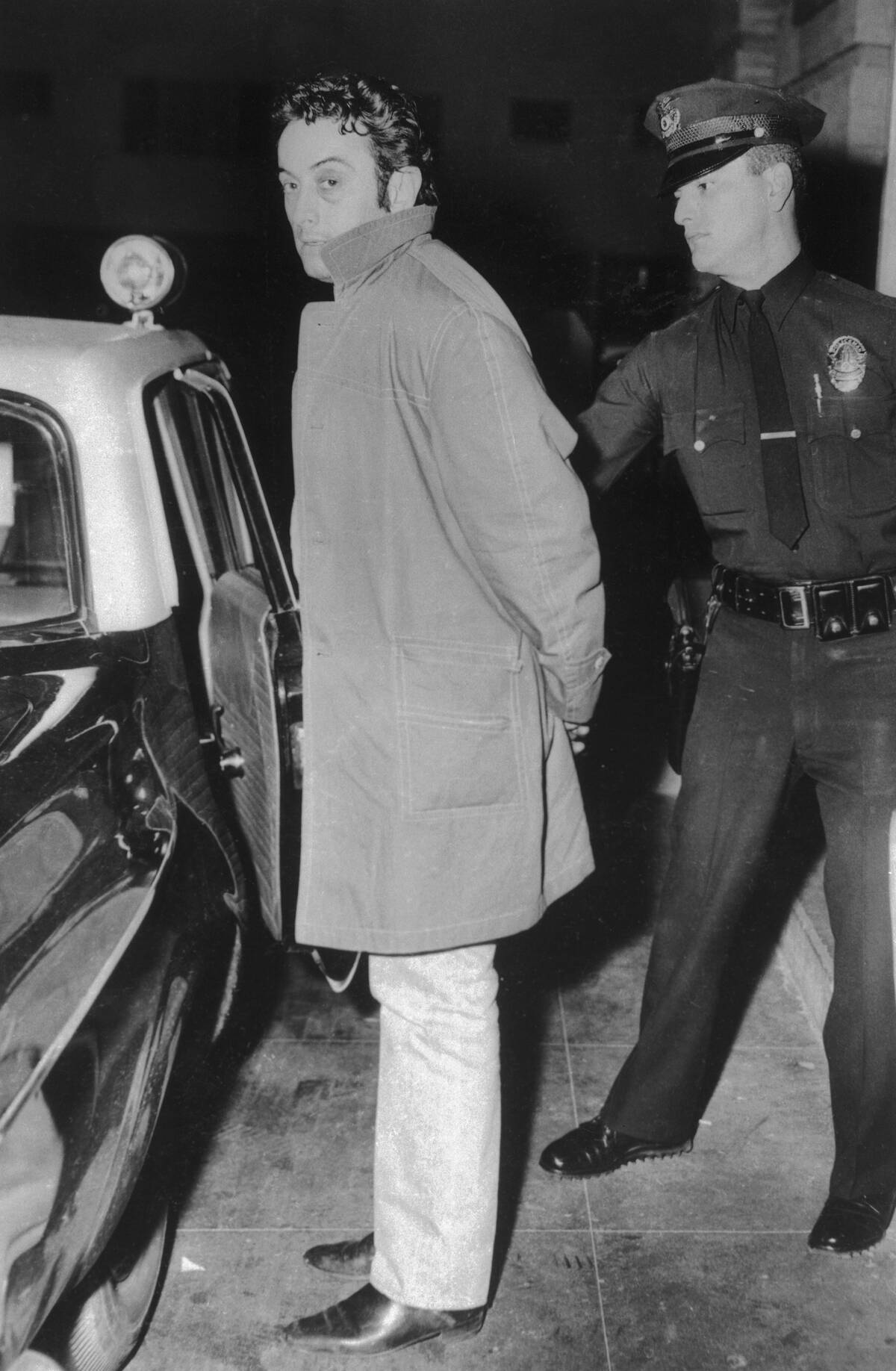

More arrests followed.

Later that same year, Bruce was arrested once more (this time for possession of controlled substances in Philadelphia).

In 1963, Bruce’s comedy once more got him into trouble, as he was arrested for using the word “schmuck” — a Yiddish insult that can also be used to reference male genitalia.

It was hard for Bruce to find bookings.

While Bruce had many powerful supporters, including figures like Norman Mailer, Hugh Hefner, and Woody Allen — his notoriety made him a controversial figure in the mainstream.

He was arrested on-stage during a performance in Chicago, and in 1963 was banned from entering the United Kingdom as he was branded by the UK’s Home Office as an “undesirable alien.”

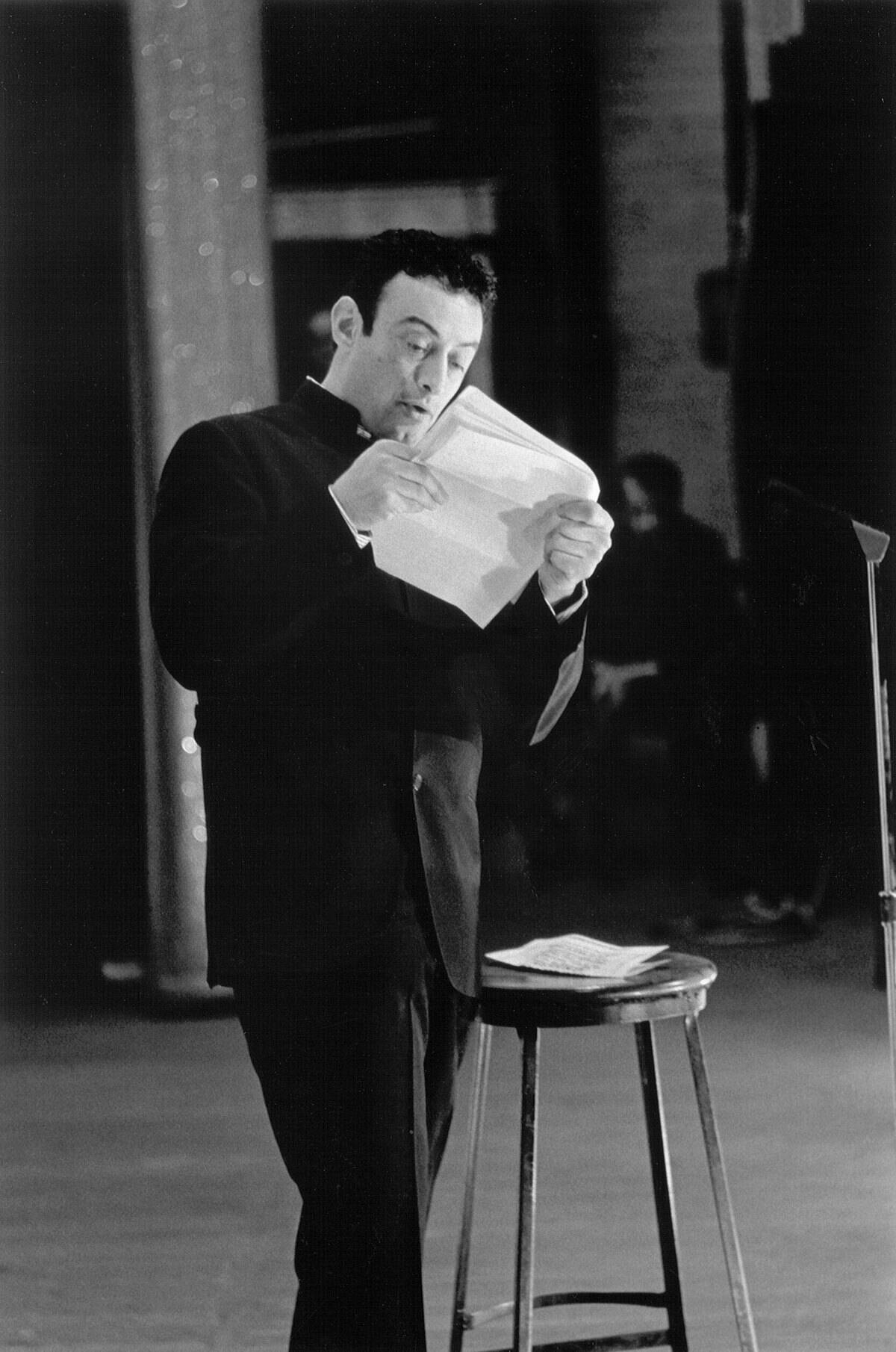

Two arrests came in April of 1964.

A complex sting operation in 1964 involved undercover detectives taking in Bruce’s shows at the Cafe Au Go Go in Greenwich Village. He was arrested twice during this period, and charged with obscenity.

This trial, unlike the San Francisco trial of 1961, was a more high-profile affair. Three judges deliberated over the six-month trial, which was covered extensively by the press.

Despite support, he was convicted.

In November of 1964, Bruce (along with club owner Howard Solomon) were convicted of obscenity. This came amidst high-profile support from other artists during the trial.

Bruce was sentenced to four months in a workhouse and was set free pending the results of an appeal. While his conviction would eventually be overturned thanks to efforts on Solomon’s part, this wouldn’t happen until after Bruce had died.

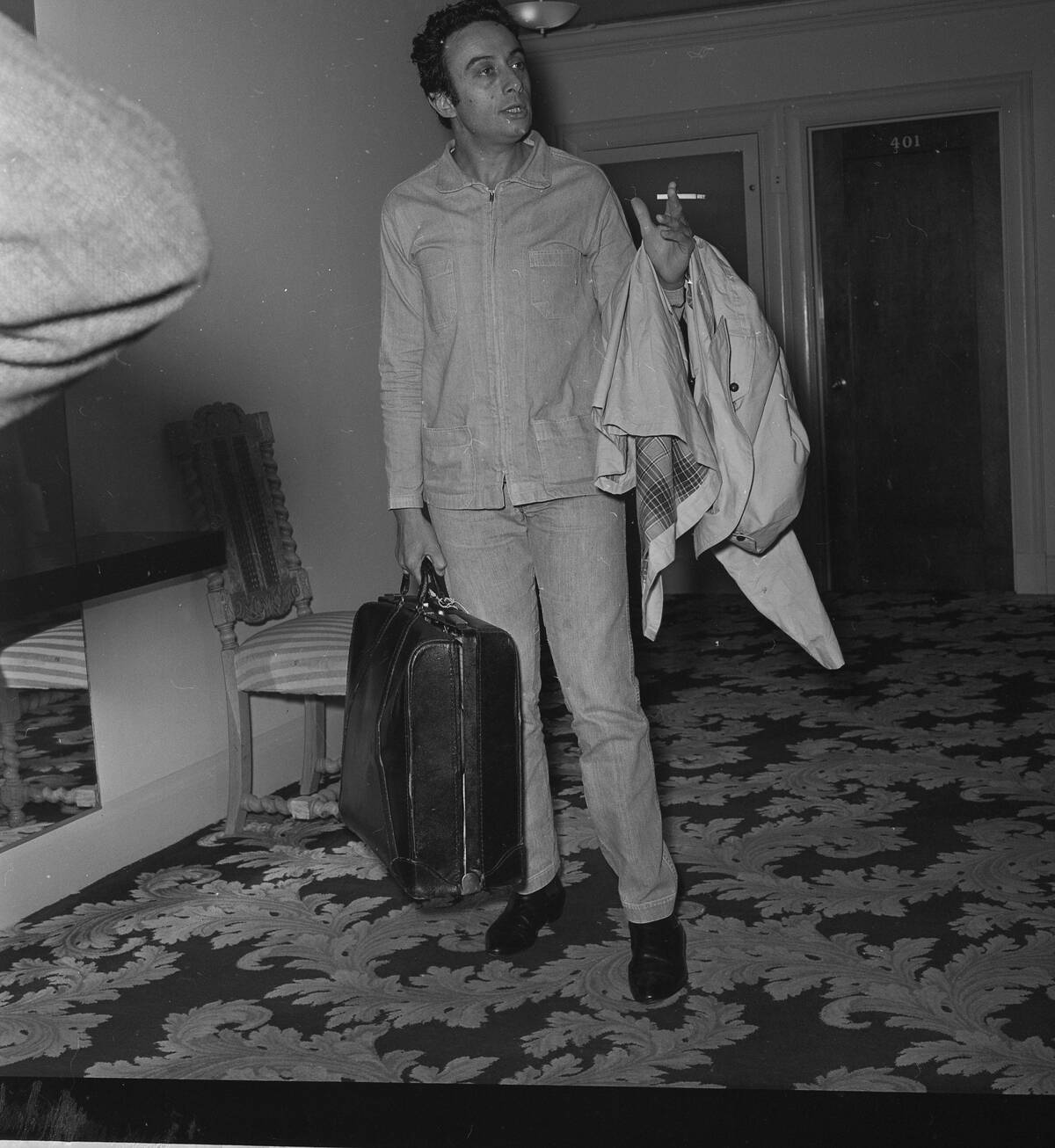

Bruce was effectively persona non grata.

Bruce’s notoriety ensured that he’d only ever appear on network television six times in his life. The negative publicity from Bruce’s various arrests and his controversial routine took its toll on the comedian.

By the mid-’60s, Bruce was in a downward spiral as he battled addictions and personal demons. During his last show, in 1966, a promoter described him as “whacked out on amphetamine.”

He was found dead on August 3, 1966.

Bruce was found lying naked on the bathroom floor, surrounded with various paraphernalia, inside his Hollywood Hills home. His official cause of death was “acute morphine poisoning caused by an overdose.”

Various memorial events in Los Angeles and New York attracted large crowds. Playboy writer Dick Schaap eulogized Bruce thusly: “One last four-letter word for Lenny: Dead. At forty. That’s obscene.”

His legacy loomed large.

In life, Bruce was a controversial figure who was largely confined to smoky comedy clubs and existed only at the edges of the mainstream — but in death, his legacy was massive.

Bruce’s autobiography, first published in a serialized form in Playboy, along with the 1974 biographical drama Lenny, helped to entrench Bruce’s legacy in the years immediately following his death.

His influence on comedy is unparalleled.

Lenny Bruce almost singlehandedly propelled standup comedy from its early days as safe, punny banter to its evolution as a boundary-pushing mirror to society.

Bruce’s work was raw, personal, and frequently vulgar. While it may have shocked audiences of the era, it’s a direct forebear to the work of comedy legends like George Carlin and Richard Pryor. Bruce was also an outsider, thanks to his many arrests — a status that gave him additional insights.

His obscenity conviction was overturned.

It may have seemed like too little too late, but in 2003 — 37 years after Bruce’s death and 39 years after his obscenity conviction — New York Governor George Pataki granted Bruce a posthumous pardon.

The ruling was noteworthy for being the first time a posthumous pardon had ever been granted in New York state. Pataki described it as “A declaration of New York’s commitment to upholding the First Amendment.”