Vintage Photos That Give Us A Look At Victorian London

London was a rapidly changing city in the late 19th century. In many ways, it was at odds with itself — while it was booming with industrial progress and was one of the most technologically advanced cities in the world, it was also plagued by poverty, overcrowding, and social inequality.

The period also became iconic thanks to the lurid saga of Jack the Ripper, who committed his murders under the cover of darkness in the grim Whitechapel district.

The identity of the city’s most famous resident is unknown.

Victorian London was home to many notable people, but historical hindsight puts Jack the Ripper first and foremost among the city’s famous residents. This is somewhat ironic, as to this day, the identity of Jack the Ripper has never been discovered.

The notorious killer is believed to have brutally murdered at least five women. It triggered widespread hysteria, media coverage, and a massive police investigation. The mystery of Jack the Ripper’s true identity would never be solved.

Regent Street was at the other end of the spectrum.

While Jack the Ripper’s hunting ground was smoggy, impoverished Whitechapel, those at the other end of the economic spectrum might be seen along Regent Street.

This iconic thoroughfare was modern by London standards, as it was designed in the early 19th century. It formed a fashionable shopping and entertainment district in the city’s West End and was lined with arcades, upscale shops, and early department stores.

The Crystal Palace was the name of a real building.

The Crystal Palace names lives on as the name of a district and a Premier League club in London, but both were named for a literal Crystal Palace.

This massive structure, made of cast iron and more than 300,000 panes of glass, was built for London’s Great Exhibition in 1851. By 1888, when this photo was taken, it had been moved to Sydenham in south London. It was a popular tourist destination for decades before it was destroyed by fire in 1936.

Working class housing was cramped.

Rowhouses are a staple of urban living throughout England, but in the late 19th century, living conditions were shockingly cramped for many working Londoners.

In poorer districts like Whitechapel and Spitalfields, multiple families could be found living in crowded tenements. The lack of sanitation led to widespread disease and high infant mortality rates. These were the conditions that inspired many notable works by Victorian authors such as Charles Dickens.

The era was named for its monarch.

Given the importance of the monarch in England, it’s no surprise that various eras are named after whoever the king or queen was at the time. This 1897 photo shows preparations for Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee, marking the 60th anniversary of the iconic queen’s reign.

While the length of Victoria’s reign was eventually bested by Queen Elizabeth II, it’s safe to say that Victoria was one of the most important monarchs in England’s history. Her reign coincided with the peak of Britain’s global dominance, along with advancements like the Industrial Revolution.

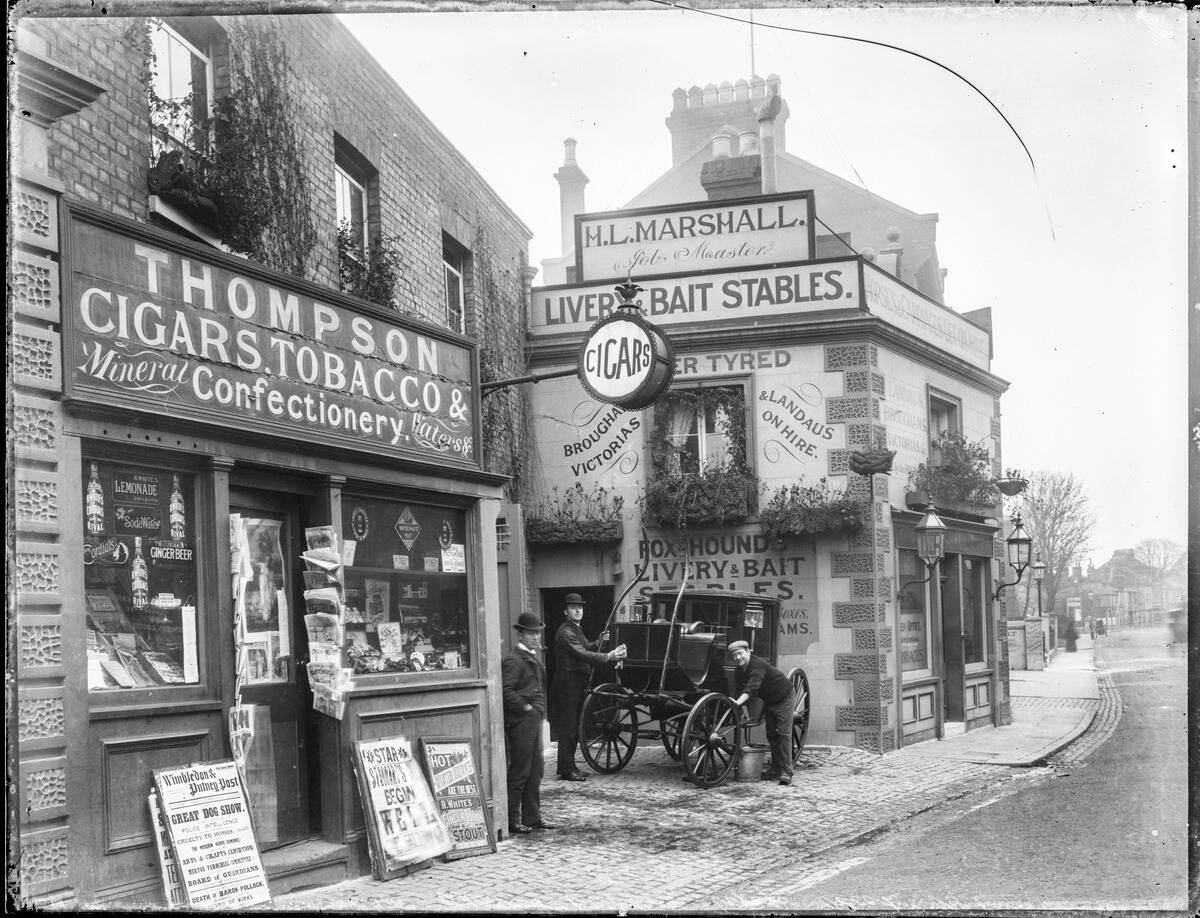

Many parts of Victorian London are gone forever.

A modern-day visit to London offers a juxtaposition of old and new, as the city’s more modern features are contrasted against historical sites. While many parts of London feel appropriately old, others have been demolished and replaced with newer structures time and time again.

This 1897 photo of Upper Richmond Road in Putney shows several hallmarks of the era, including a livery stable and candy store. Aside from a pub that isn’t quite visible, all of the buildings in this area were demolished decades ago.

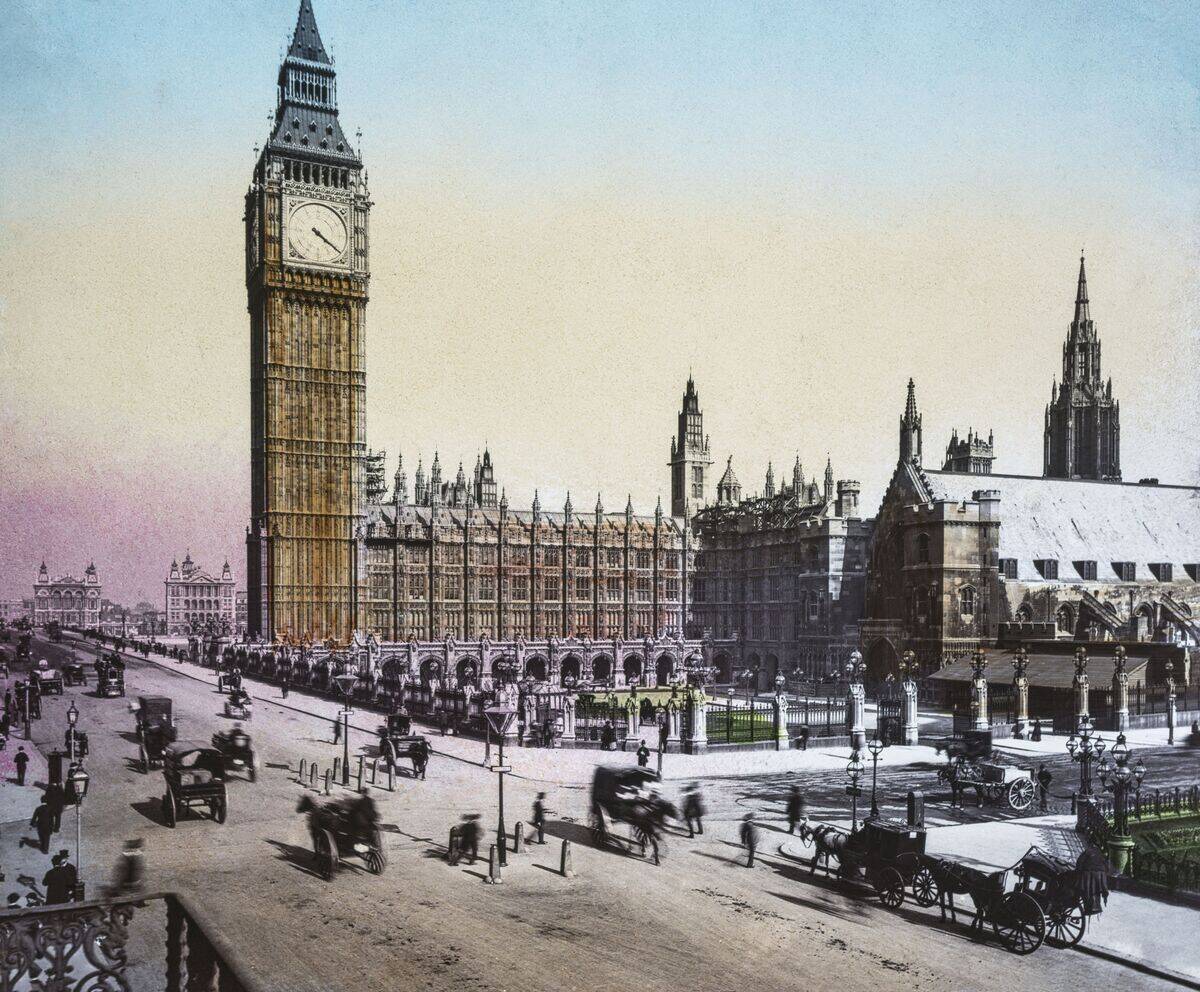

Some sights would be familiar to modern eyes.

The Houses of Parliament, officially known as the Palace of Westminster, stand to this day as an icon of not just London, but England as a whole.

The sprawling complex was relatively new in the late 19th century, as it had been rebuilt in the Gothic Revival style after a devastating fire in 1834. Its iconic clock tower was completed in 1859. While it was officially known as Elizabeth Tower, it was officially renamed Big Ben — its longtime nickname — in 2012.

The railway was king.

The advent of railroads helped fuel the Industrial Revolution, as trains were well equipped to transport large quantities of goods and materials. Trains were also useful for transporting people, and by the late 19th century, London was crisscrossed with train tracks and had many large stations.

St. Pancras Station, seen here, was a showcase of Victorian engineering and architecture. At the time of its grand opening in 1868, it featured the largest single-span roof in the world.

Double-decker buses existed, kind of.

Spotting a bright red, double-decker bus is a quintessentially London experience in modern times, and this photo shows that double-decker buses were traversing London’s streets as far back as the 19th century.

Of course, this double-decker bus isn’t powered by a motor and is instead led by a pair of horses. While those who were more wealthy might use a smaller horse-drawn cab, these larger buses offered affordable transportation for working-class people.

Electric vehicles were a thing as well.

Electric vehicles are seen as a modern-day innovation, but they’ve actually existed in a limited form since the dawn of motor vehicles — even if they were largely a novelty.

This turn of the century photo shows an electric car, which would have been a rare sight at the time. This model weighed about two tons and could travel 30 miles before it needed to be recharged. In time, gas-powered vehicles would take over, and much later on, electric vehicles came back in a more widespread way.

The East End was overcrowded and impoverished.

This photo shows an area known at the time as the “Jewish Ghetto” of London, which became home to Jewish refugees escaping pogroms and persecution throughout Eastern Europe.

While the influx of immigration provided rich cultural traditions and community organizations, conditions in the area were harsh, with its residents facing frequent anti-Semitism.

The era had unique weather conditions.

London in the late 19th century featured some unusual atmospheric conditions, from its notorious smog (brought on by pollution) to unusually chilly conditions. While the “Little Ice Age” that began in the 16th century ended in the mid-19th century, London endured more bone-chilling temperatures close to the turn of the 20th century.

The Great Frost of 1895 was one of the harshest winters to hit London during this period, with the city enduring subzero temperatures for months. While this led to hardships for many, it also created ideal skating conditions.

Gas lamps added ambience.

Photographic technology of the time doesn’t allow for images that accurately capture the gaslit, smoggy gloom of nighttime in Victorian London, but this engraving showing Westminster Bridge provides some idea.

Gas lamps were a significant innovation, lighting areas much more effectively and safely than candles and oil lamps. Still, they weren’t nearly as bright as modern electric lighting, and they added a flickering, eerie atmosphere to London’s Victorian nights.

A famous landmark was built.

Tower Bridge (often erroneously called London Bridge) is one of London’s most enduring symbols, so it may come as a surprise that this iconic bridge barely predates the 20th century.

This 1893 photo shows the final stages of the bridge’s construction. It’s a unique structure, featuring a drawbridge mechanism flanked by two neo-Gothic towers that fit in thematically with the nearby Tower of London.

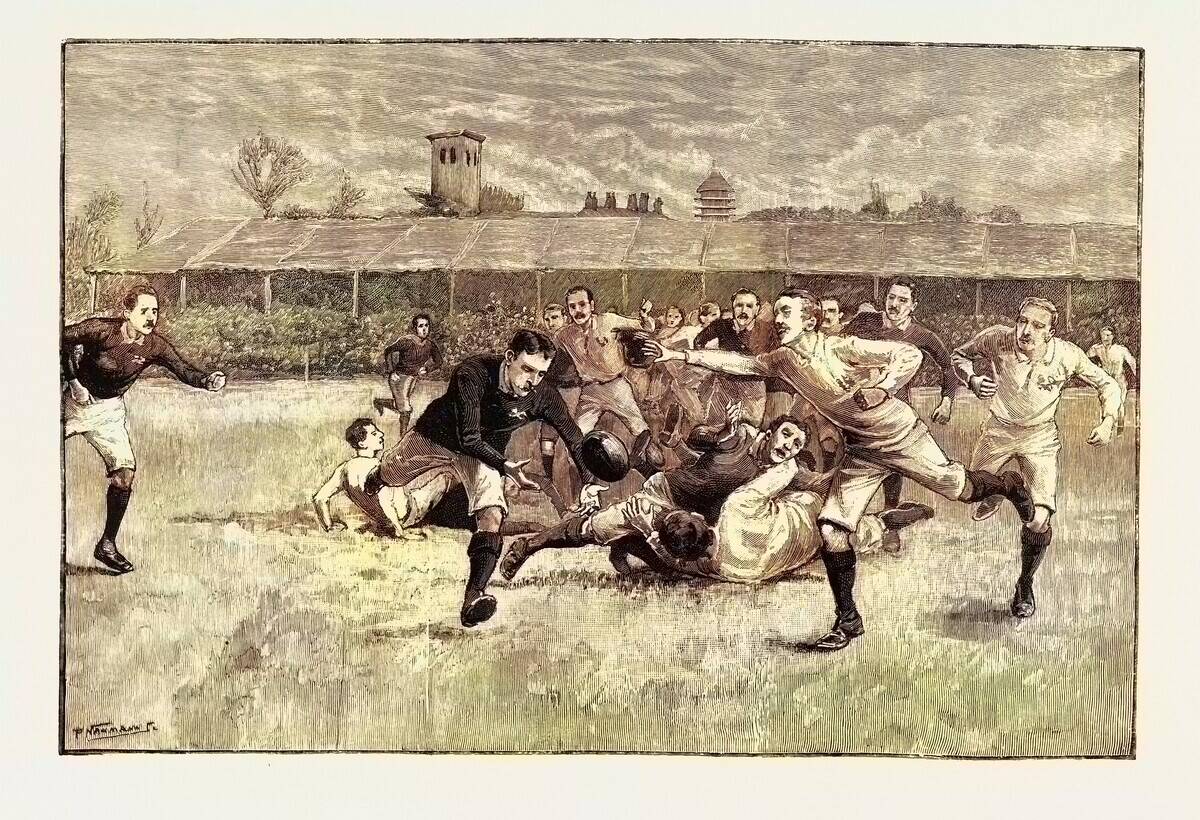

Spectator sports were coming into their own.

The evolution of football dates back to the loosely-organized medieval sport of town ball, and by the 19th century, various rulesets had emerged (mostly stemming from rugby).

The Football Association — to this day, England’s governing body for football/soccer — was founded in 1863 and helped to unify the rules, which in turn made the game more structured and popular. It was during this era that many of London’s iconic clubs and stadiums first emerged.