Photos Showing The Fascinating Early Days Of NASA

Well over half a century since NASA first landed men on the moon, it’s easy to take for granted just how significant this achievement was. When the space race began, America was losing badly — but within just a few short years, NASA was able to pull ahead.

These weren’t easy years, as they were marked by setbacks and tragedy. But as the world watched on, NASA edged its way closer and closer to the moon — finally touching down in 1969.

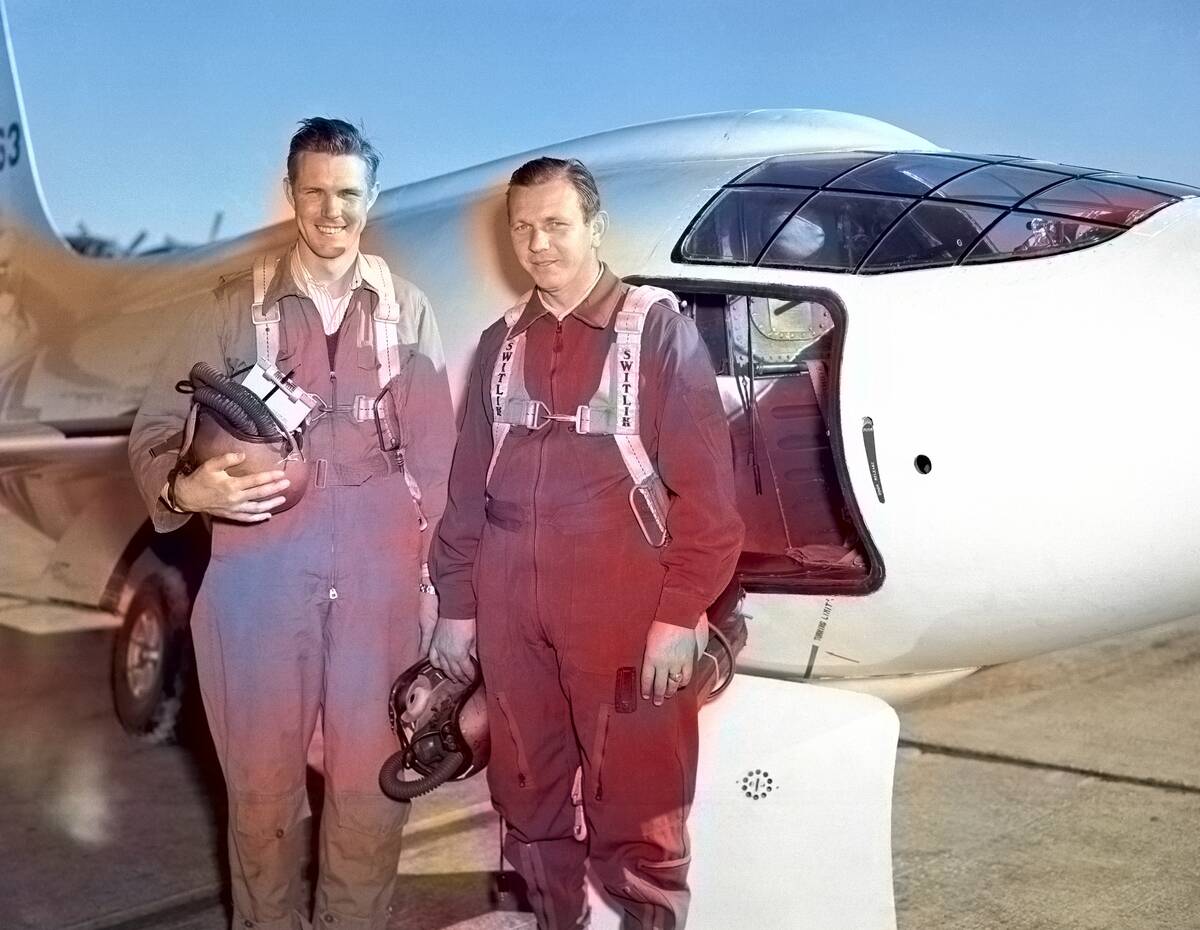

NACA was its predecessor.

Before the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, or NASA, there was NACA — the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, which was established all the way back in 1915.

NACA spent its early decades focusing on aeronautical research, and employed test pilots like the men seen above to fly experimental planes. After the Soviet Union launched Sputnik in 1957, the United States quickly re-evaluated its space program. In 1958, NASA was officially formed, absorbing NACA’s personnel, research facilities, and ongoing projects. It was essentially NACA, but with a much broader, space-focused mandate.

The Mercury 7 were NASA’s first astronauts.

This photo shows the introduction of NASA’s first seven astronauts — from left to right, Walter “Wally” Schirra, Alan Shepard, Virgil “Gus” Grissom, Donald “Deke” Slayton, John Glenn, Scott Carpenter, and Gordon Cooper.

The high-profile nature of the early space program made all of these men instant celebrities. The Mercury program was a hesitant start to NASA’s space program, but it helped the United States to make up lost ground against the Soviet space juggernaut.

In 1961, Alan Shepard went to space.

The Mercury-Redstone 3 mission, also known as Freedom 7, marked America’s first manned spaceflight — and Alan Shepard was given the honor of piloting it. It was a brief mission, reaching a suborbital altitude of 116 miles and lasting just over 15 minutes.

While most of the flight was automated, Shepard demonstrated manual control for parts of it — serving as a proof-of-concept that astronauts could handle real-time decision making in space. The successful touchdown made Shepard the most famous American astronaut at the time.

John F. Kennedy pledged to go to the moon.

In a landmark 1962 speech at Rice University, President John F. Kennedy announced an incredibly ambitious goal: The intention to land a man on the moon, and return him to Earth, by the end of the decade.

Kennedy famously stated “We choose to go to the moon — not because it is easy, but because it is hard.” It helped to frame space exploration as both a technological and moral achievement, and in turn made the public enthusiastic at the prospect of landing on the moon.

The general public was enthusiastic.

It’s safe to say that America had space mania in the 1960s, and NASA’s achievements were heralded as the pinnacle of technological innovation.

These boys are seen gathered around the Friendship 7 space module during the 1964-65 World’s Fair in New York. Friendship 7 was the module that carried John Glenn into orbit in 1962, making him the first American to fully orbit Earth.

The Gemini program supplanted Mercury.

While the Mercury program accomplished its aims of getting astronauts into orbit, the subsequent Gemini program had a more specific goal: To develop and test the technologies and techniques that would be necessary for an eventual moon landing.

Astronauts James McDivitt and Edward White, seen here, took part in the Gemini 4 mission. They spent over four days in space, a record at the time. This demonstrated the fact that astronauts could spend an extended period in space, which would be necessary for any moon landing.

Gemini 4 broke new ground.

McDivitt and White didn’t just demonstrate the feasibility of extended stays in space, they also worked on space rendezvous and docking with target vehicles — both of which would be critical in any moon landing.

Most dramatically, Gemini 4 also featured the first American spacewalk. Ed White floated outside the spacecraft for about 23 minutes while tethered to the craft and using a gas gun for maneuvering.

It became a spectator sport.

The spectators seen here are watching the launch of Gemini VIII, piloted by Neil Armstrong and David Scott in March of 1966. Gemini VIII was historic for marking the first successful demonstration of docking two vehicles while in orbit.

Despite this, disaster nearly struck as a malfunctioning thruster caused the spacecraft to spin uncontrollably. Armstrong was cool under pressure and was able to use the reentry control thrusters to stabilize the craft.

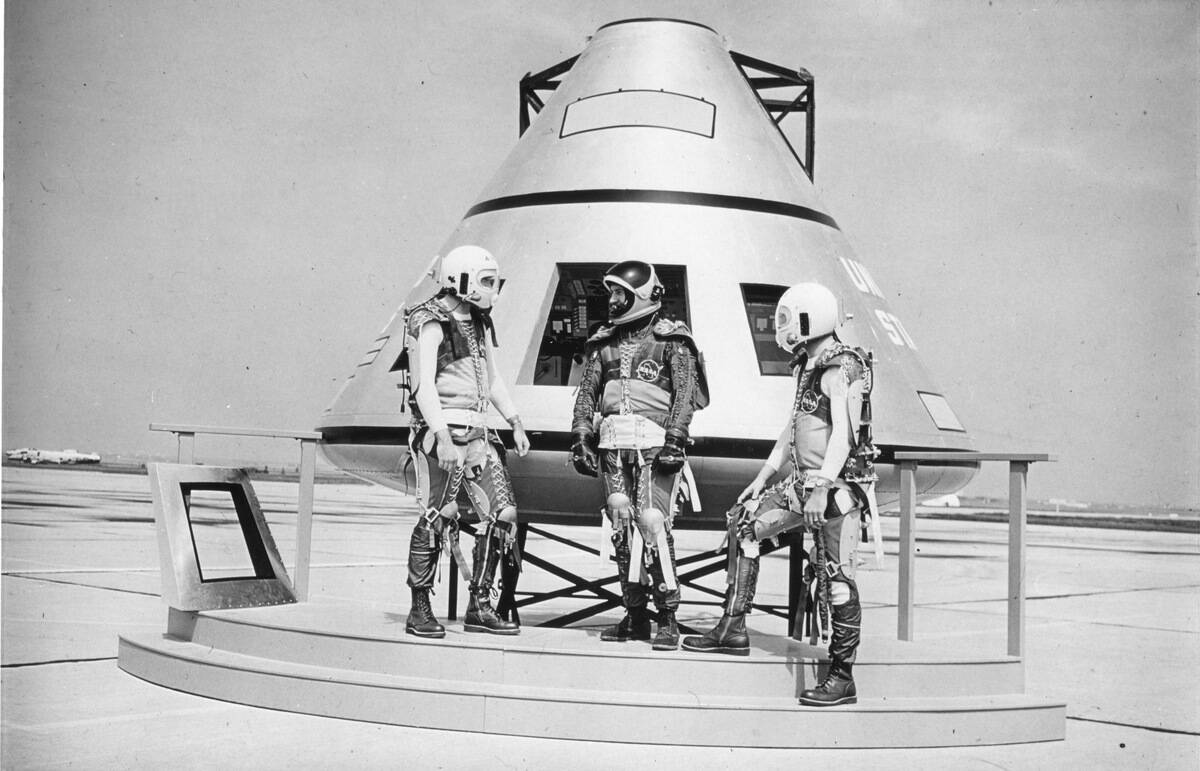

The moon was always the goal.

At the time this photo was taken, in 1962, America was still seven years away from landing on the moon and still in the thick of the pre-Apollo Gemini program. Despite this, engineers were already clearly working on Apollo’s lunar lander.

The final capsule wasn’t a direct copy of this mockup, but it wasn’t far off either. It consisted of two stages — the descent stage, which could touch down gently using landing gear and engines, and the ascent stage, which used rockets to lift back into orbit.

They had to train for the moon while on Earth.

This unusual-looking device is the Lunar Landing Research Vehicle, or LLRV. It never got close to space, and was instead designed to simulate the low gravity of the moon while still on Earth.

The device used jet engines and a vertical thruster system to counteract most of its weight, in turn simulating weightlessness. While it was notoriously difficult to fly and was crashed repeatedly, it was a critical learning tool for astronauts as they prepared to go to the moon.

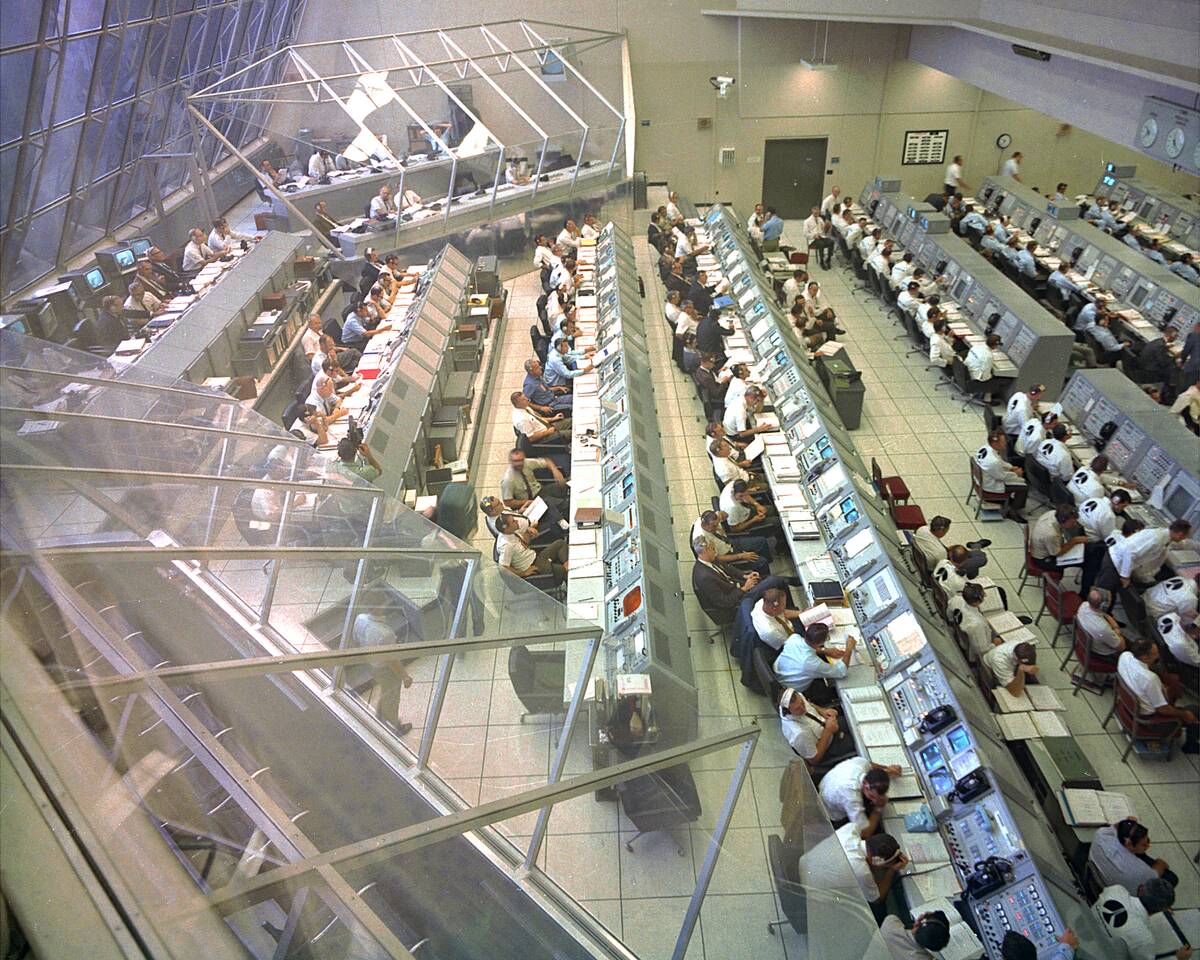

Each mission required a massive team.

The astronauts on each flight tended to get much of the glory in the public eye, but none of it would have been possible without the hard-working engineers and scientists at NASA’s Launch Control Center.

The LCC was effectively NASA’s nerve center, featuring banks of consoles and early computers that could communicate with astronauts and tracking stations around the world.

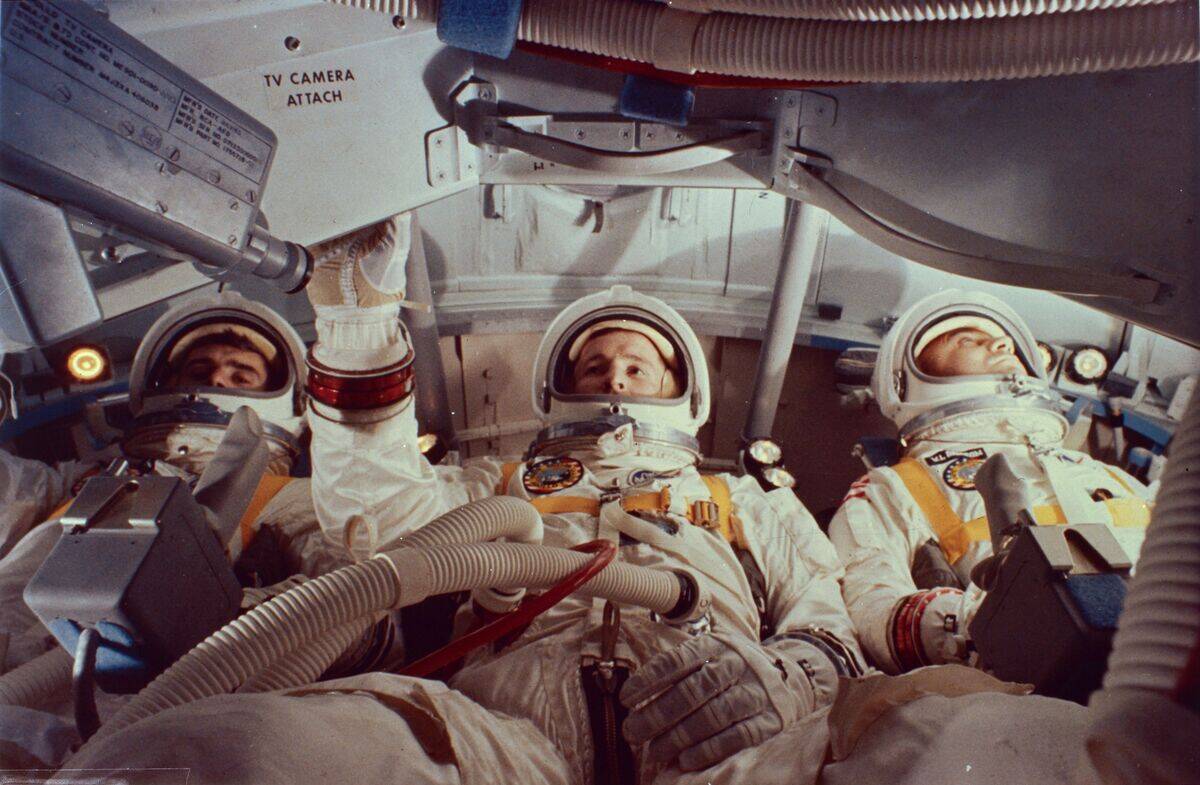

The Apollo program got off to a tragic start.

The Apollo program had the optimistic goal of landing men on the moon, but its first mission, Apollo 1, resulted in the deaths of three astronauts — Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee, seen here.

The astronauts were taking part in a pre-launch test when a fire broke out in the sealed, oxygen-rich cabin. The astronauts were unable to escape, and the hard-earned lessons of the tragedy helped to shape the Apollo program moving forward.

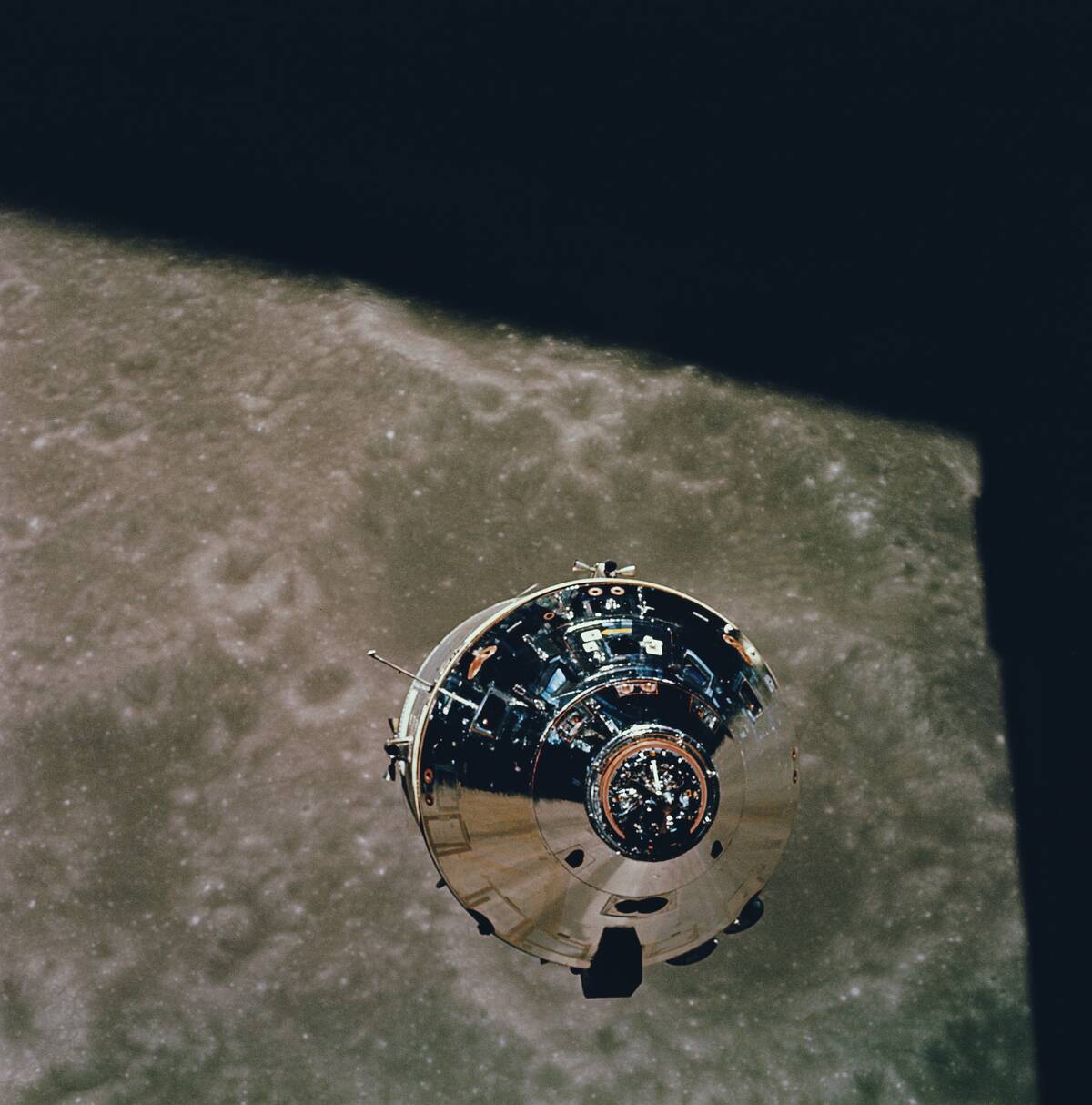

Apollo brought America very close to the moon.

Apollo’s missions got closer and closer to the moon, ahead of Apollo 11’s eventual landing. This photo shows the mission just before Apollo 11 — Apollo 10 — which served as a kind of dress rehearsal for the landing.

The mission tested all aspects of a lunar landing except for the actual touchdown, and the module descended to within 8.5 miles of the lunar surface.

On July 20, 1969, history was made.

The moon landing of July 20, 1969, was perhaps the 20th century’s most iconic moment, as Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin touched down on the lunar surface (the third astronaut, Michael Collins, had to remain in orbit).

The astronauts spent about two and a half hours on the moon, exploring, collecting samples, and deploying experiments. The historic event was broadcast live to millions watching on television.

On July 24, 1969, they returned.

Landing on the moon accomplished half of JFK’s goal, while the other half — returning safely to Earth — was critically important. Aldrin and Armstrong ascended in the lunar module’s ascent stage to rendezvous in orbit with Collins and head home.

On July 24th, four days after the historic landing, the three astronauts splashed down safely in the Pacific Ocean, where they were recovered by the USS Hornet, an aircraft carrier. They can be seen wearing isolation garments in this photo, as it was unknown if they’d picked up any pathogens on the moon.