Calendars from antiquity measuring solar and lunar time

Ancient calendars were more than just tools for tracking days; they were crucial for agriculture, religious rituals, and societal organization. They helped civilizations predict seasonal changes, which were vital for planting and harvesting crops.

The way societies structured their calendars often reflected their cultural priorities and understanding of the universe. From the pyramids of Egypt to the temples of the Mayans, ancient calendars have left an indelible mark on history, showcasing humanity’s early attempts to make sense of time.

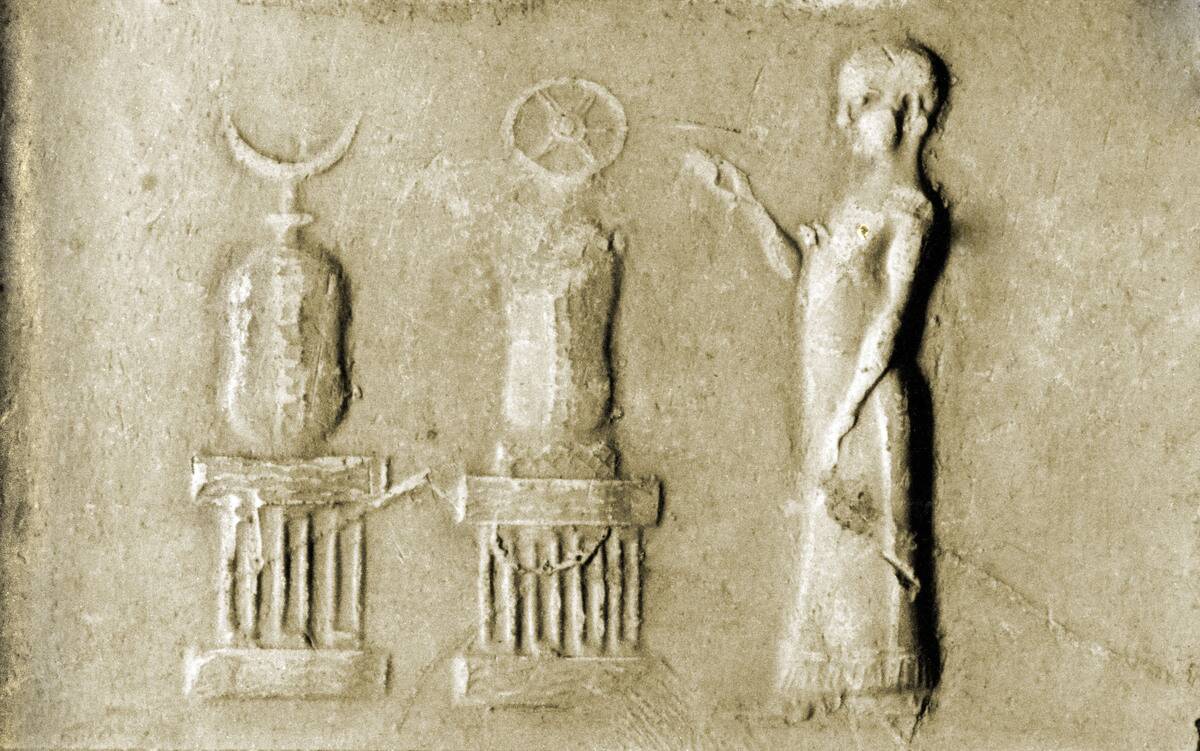

The Mesopotamian Calendar: Pioneers of Timekeeping

The Mesopotamians were among the first to develop a sophisticated calendar system. It was lunisolar, incorporating both lunar months and solar years, consisting of 12 months with an occasional leap month to stay synchronized with the seasons. This calendar was essential for their agricultural and religious activities.

Mesopotamian astronomers meticulously observed celestial bodies, laying the groundwork for future advancements in astronomy and calendar-making. Their contributions underscore the ingenuity of early civilizations in understanding and harnessing time.

The Egyptian Calendar: A Gift from the Nile

The ancient Egyptians developed a calendar based on the annual flooding of the Nile, which was crucial for their agriculture. It consisted of 12 months of 30 days each, with an additional five epagomenal days to complete the solar year.

This structure aligned with their religious beliefs, as each month was dedicated to a particular deity. The precision of their calendar reflects their advanced understanding of astronomy and its profound impact on their civilization, influencing timekeeping systems for millennia.

The Mayan Calendar: Masters of Astronomy

The Mayans were renowned for their complex calendar systems, which included the Tzolk’in and Haab’, blending religious and solar cycles. Their Long Count calendar, famous for its supposed 2012 prophecy, tracked longer astronomical cycles over thousands of years.

The Mayans’ deep astronomical knowledge allowed them to predict solar eclipses and other celestial events with remarkable accuracy. Their calendar was not only a tool for timekeeping but also a testament to their sophisticated understanding of the cosmos.

The Chinese Calendar: Harmony of Sun and Moon

The Chinese calendar is a lunisolar system, balancing lunar months with solar years. It features a sophisticated 60-year cycle, combining 12 animal zodiac signs with five elements. This calendar’s design reflects a deep connection between cosmic cycles and human life, influencing festivals, agricultural practices, and astrology.

Celebrations like the Lunar New Year demonstrate their cultural significance. This harmonious blend of celestial elements mirrors the Chinese philosophy of balance and has persisted for millennia, showcasing its enduring importance.

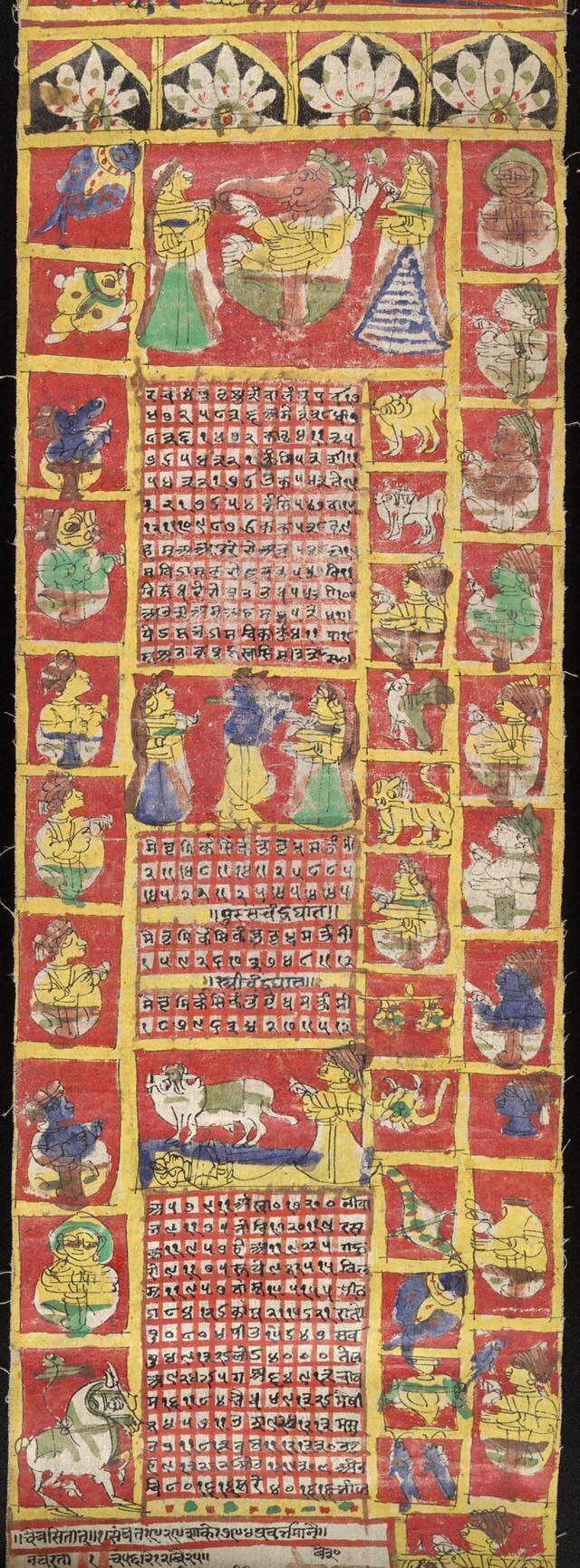

The Hindu Calendar: A Spiritual Timekeeper

The traditional Hindu calendar, or panchangam, intricately weaves together lunar and solar elements, with variations across regions. It is used to determine auspicious times for festivals, agricultural rituals, and daily activities. Divided into lunar months, it includes leap months to align with the solar year.

The calendar’s spiritual significance is profound, guiding religious observances and personal milestones. Its adaptability and spiritual depth illustrate the enduring relationship between timekeeping and Hindu cosmology, reflecting a culture deeply attuned to cosmic rhythms.

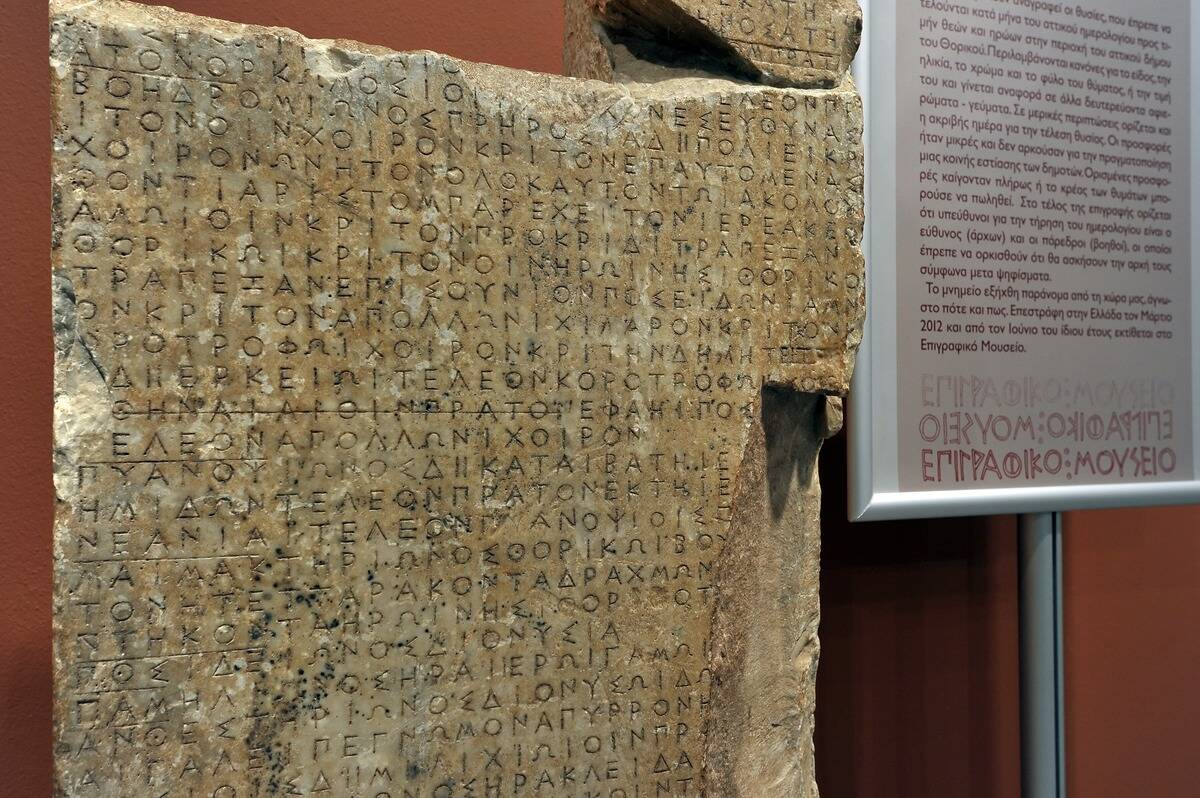

The Greek Calendar: Olympian Timekeeping

The ancient Greeks employed various calendar systems, often reflecting regional differences. The Attic calendar, used in Athens, was lunisolar, comprising 12 or 13 months. It was closely linked to the timing of religious festivals, including the famous Olympic Games.

Greek calendars played a vital role in coordinating civic and religious life, illustrating the integration of timekeeping with cultural and social activities. Their approach to calendars showcased a blend of practicality and devotion, influencing timekeeping in the Mediterranean region.

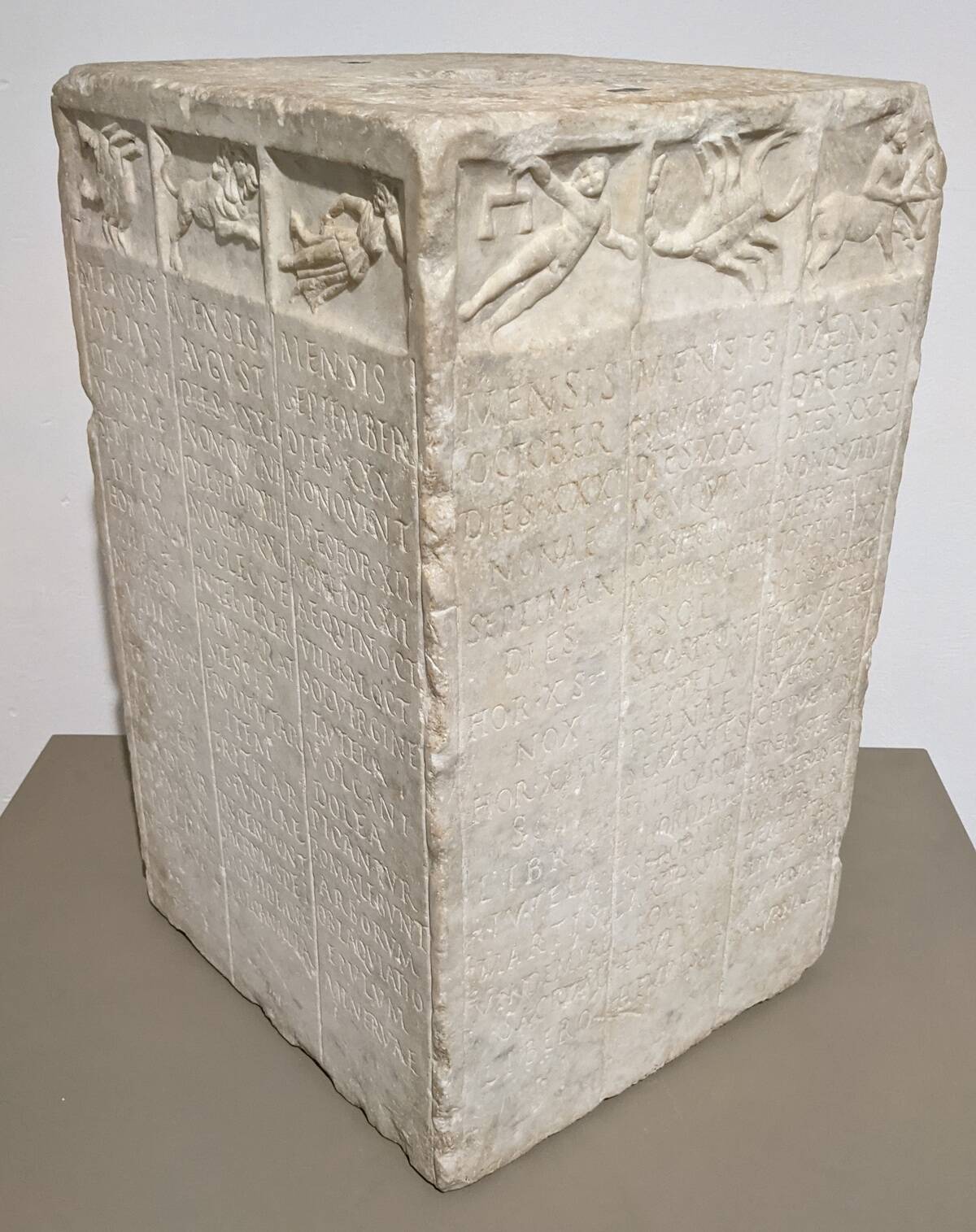

The Roman Calendar: From Romulus to Julian

Initially, the Roman calendar was a lunar system with ten months, attributed to Romulus. Later, Numa Pompilius added January and February, bringing it closer to a solar year. The Julian calendar, introduced by Julius Caesar in 46 BCE, reformed the calendar to a solar system with 365 days and a leap year.

This calendar provided greater accuracy and stability, influencing Western timekeeping systems for centuries. The transition from lunar to solar reflects Rome’s evolution from a fledgling city-state to a mighty empire.

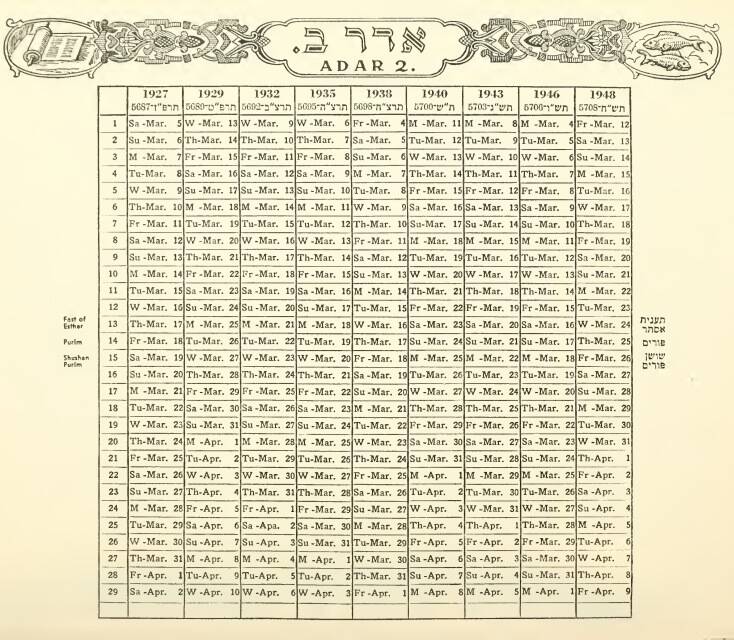

The Hebrew Calendar: A Cycle of Festivals

The Hebrew calendar is lunisolar, with 12 lunar months and an extra month added seven times in a 19-year cycle to align it with the solar year. It is intrinsically tied to Jewish religious life, determining the dates of festivals and significant events.

This calendar reflects a deep spiritual connection with time, emphasizing cycles of renewal and observance. Its structure ensures that festivals occur in their appropriate seasons, preserving traditions and cultural identity over millennia, a testament to its enduring significance.

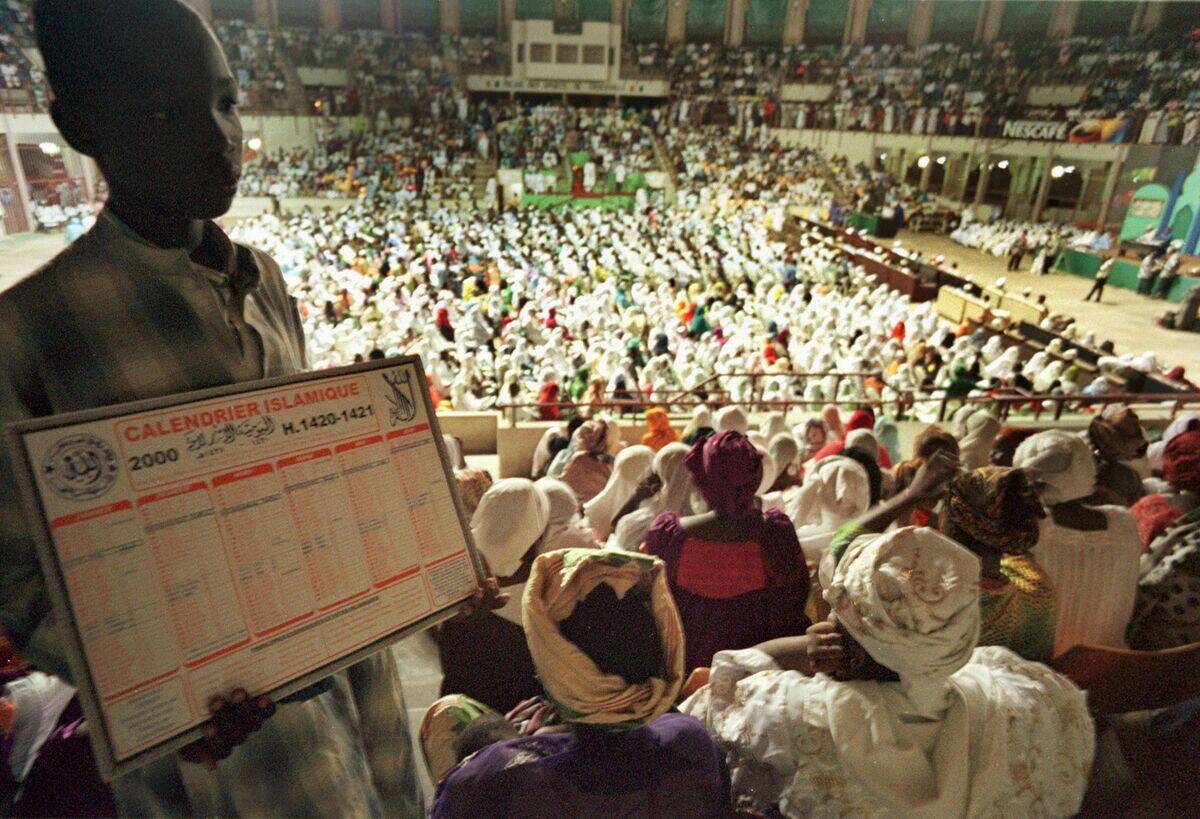

The Islamic Lunar Calendar: A Reflection of Faith

The Islamic calendar, or Hijri, is purely lunar, consisting of 12 months of 29 or 30 days. It is used primarily to determine the timing of religious observances, such as Ramadan and Hajj.

This calendar’s lunar nature means it does not align with the solar year, causing Islamic months to shift through seasons over time. The Hijri calendar reflects a spiritual rhythm, emphasizing the moon’s role in Islamic faith and practice, with its cyclical nature reinforcing the concept of continual spiritual renewal.

The Inca Calendar: Sun Worship and Agriculture

The Inca civilization developed a solar calendar that was closely tied to agricultural cycles and sun worship. They divided the year into 12 months, each associated with specific agricultural tasks and religious ceremonies.

The Inti Raymi, a festival honoring the sun god Inti, marked the winter solstice and was a key event in their calendar. The Inca’s reliance on solar observations for timekeeping underscores their reverence for the sun and its central role in their culture and daily life.

The Aztec Calendar: The Stone of the Sun

The Aztec calendar was a sophisticated system comprising the Tonalpohualli, a 260-day ritual calendar, and the Xiuhpohualli, a 365-day solar calendar. These intertwined cycles reflected a complex understanding of cosmology and time.

The famous Aztec Sun Stone (pictured), often mistakenly called a calendar, represents their cosmic vision and the cyclical nature of time. The Aztec calendar played a crucial role in religious ceremonies and agricultural planning, illustrating the integration of timekeeping with their spiritual and societal frameworks.

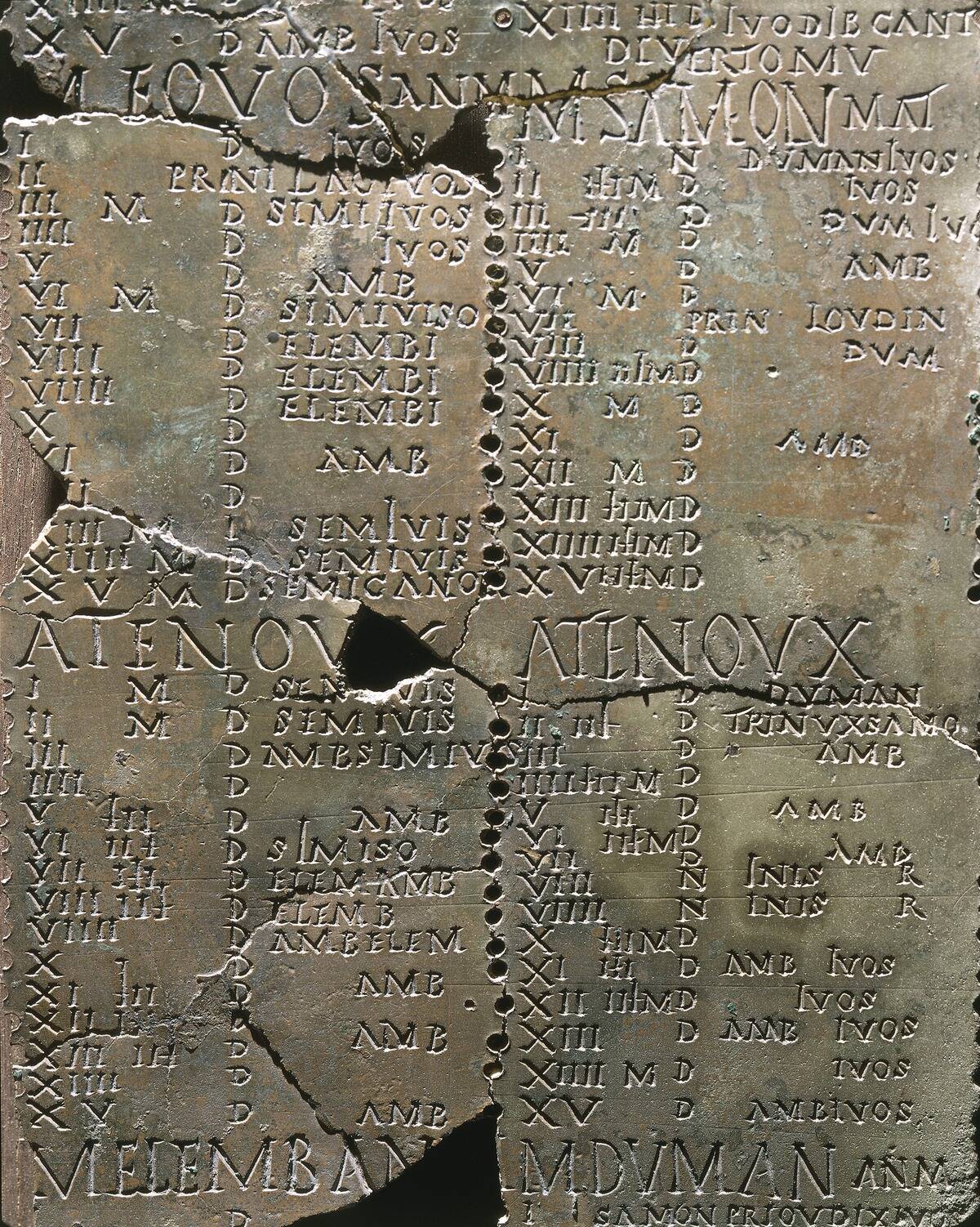

The Celtic Calendar: Seasons of the Earth

The Celtic calendar was closely linked to the natural world, marking the changing seasons and agricultural cycles. It divided the year into eight festivals, including Samhain and Beltane, which celebrated significant turning points in the natural year.

This calendar emphasized harmony with nature, reflecting the Celts’ deep connection to the earth and its rhythms. The cyclical nature of their calendar underscored the importance of renewal and continuity, highlighting the integration of timekeeping with cultural and spiritual life.